Hello from Chinarrative.

Stories about suicide pose ethical dilemmas for publishers. However, we feel that the longread presented in this edition of our newsletter, which deals with the subject, is one worth sharing.

In it, we learn about the rise of online suicide pact groups in China and meet some of the people who are trying to infiltrate them to prevent needless deaths. People such as Hu Ming, who assumed the role of “pro-life counselor” shortly after his own son, Xiaotian, killed himself as part of chat group pact.

Still, some subscribers may find details in the story disturbing and so we encourage reader discretion.

Life, Death of Suicide Chat Groups

By Yang Yuying and Ren Wu

Hu Xiaotian* died on a day in May.

He had been contemplating suicide for two years. So he formed a suicide pact with two companions he met in a suicide chat group on messaging app QQ.

The group traveled to Wuhan and killed themselves by burning charcoal in a sealed room. Hu Xiaotian was a “success story” of sorts in his chat group.

His father, Hu Ming, infiltrated the chat group after his son’s suicide, becoming a “pro-life” counselor. Hu Ming tried to pull young men and women enveloped in darkness back from the brink.

For more than two months, he went from scouring for clues to his son’s suicide to intense self-blame, to trying to redeem himself by counseling members of suicide chat groups, to utter devastation after failed attempts.

In the end, Hu Ming decided he needed a break from the swamp of depression that the chat groups represented. So he deleted all his friends and media contacts on QQ. The afternoon he vanished from the messaging app, he broke down in tears at home alone.

Missing Son

Hu Ming can still clearly remember that Xiaotian left home at 5:58 p.m. on May 22. That was the last time he saw his son alive.

Hu Ming was preparing dinner in the kitchen. He noticed Xiaotian emerging from the bathroom smelling of cologne. He even kidded:

What’s a boy doing smelling so good?

Xiaotian flashed an embarrassed smiled and said he was “off to Beijing,” then left. He stayed in touch with his family during the first three days after his departure.

On May 25, his family sent him a message to remind him that he had a small operation scheduled for May 27 and to return in time. Xiaotian messaged back saying not to worry. A day before the surgery, Xiaotian stopped responding to messages and answering his phone. His Fitbit-like workout level on [the social media platform] WeChat dropped to zero.

Hu Xiaotian was missing.

Shortly before 11 p.m. on May 28, just as he was about to go to bed, Hu Ming received a screencap of a QQ conversation from Xiaotian’s girlfriend.

In the conversation, Xiaotian and his QQ friends were discussing ways of committing suicide. The terms that appeared in the conversation—plastic strips, charcoal bins and sleeping pills—terrified Hu Ming.

He started panicking. His wife was already sound asleep because she had to work the early shift the next day, so Hu Ming messaged a few relatives for advice. They all agreed that suicide was unlikely and that the conversation was likely a prank. Hu Ming was confident that Xiaotian would return soon.

Yet there was still no word from Xiaotian by the evening of June 2. Xiaotian’s WeChat workout ranking plummeted. Hu Ming felt something was wrong. He called the nearest police station. The next day officers confirmed that Xiaotian had taken a high-speed train to Wuhan and checked into a local hotel.

On June 4, Hu Ming and his wife rushed to Wuhan and reported the matter to local police. Hu Ming wasn’t a stranger in the central Chinese city. Hu Ming’s family was the catering contractor at a local hotel for 15 years until 2009. But walking the streets of Wuhan once more, Hu Ming and his wife felt they were treading on foreign soil. Where would they start?

After a day of fruitless searching, Hu Ming sat on the sidewalk late that night and broke down crying. “Something must have happened to him,” Hu Ming uttered to himself. A deep sense of unease nagged at Hu Ming those few days, just like the brutal June heat of Wuhan.

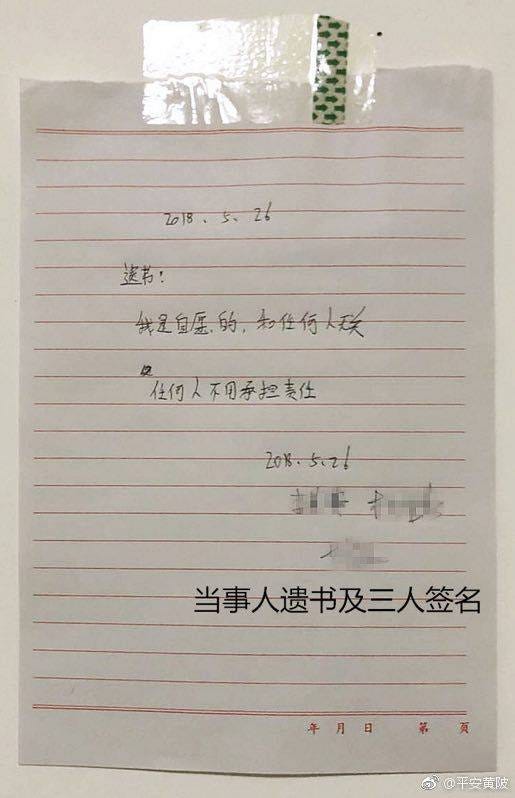

The suicide note of the three young men who killed themselves in the central city of Wuhan after forming a death pact online. Image from Weibo account @平安黄陂.

On June 8, Wuhan police notified Hu Ming that they found the bodies of three young men in a rental apartment. Also present was a basin filled with burnt wood charcoal and a suicide note saying that “no one was responsible for their deaths.” The letter was signed by three people, one of whom was Hu Xiaotian.

At a local funeral parlor in Wuhan, Hu Ming cursed and howled as he cradled his son’s icy corpse in his arms. Recalling the scene later, Hu Ming said, “My world had never felt darker.”

Hu Ming couldn’t for the life of him understand why Xiaotian wanted to die by suicide. He was financially well-off and in good health. After graduating from junior high school, he joined the family fashion business. He got along with his parents and business was good. There were no signs of tension in his yearlong relationship with girlfriend Liu Ting, despite it being long-distance.

Hu Ming asked Liu Ting for Xiaotian’s QQ account number and password. The 46-year-old started learning how to use QQ, bit by bit, in a bid to understand his late son’s inner world.

Hu Ming logged on as Hu Xiaotian. When Hu Xiaotian’s grey profile pic lit up again, quite a few of his suicide chat group buddies were spooked. Some even sent private messages to “Hu Xiaotian” asking why his suicide attempt failed.

Among Hu Xiaotian’s outstanding friend requests were several people seeking to form suicide pacts. Faced with the flurry of messages and phrases about suicide, Hu Ming was shocked, nervous and terrified. At one point, he had doubted the very existence of suicide chat groups.

Suicide chat groups are sanctuaries staking out a dark corner in the vast, danger-filled world that is the internet. Members come with their own unique baggage—some are determined to die, some hoping for a sympathetic ear and others looking to form suicide pacts. Hu Ming only belatedly found out that Hu Xiaotian had long been a chat group member before his suicide and had formed a suicide pact with two fellow members.

Hu Ming tried to trace his son’s online movements and comments before his death. In the few screencaps of conversations that he could get his hands on, Xiaotian was a major player. His son sounded like a veteran, outlining in detail the steps to dying by suicide.

The screencap of Xiaotian’s instructions were even widely circulated online as a de facto manual for suicide by charcoal burning, so much so that in their conversations with Hu Ming, some chat groups members jokingly referred to his son as a “suicide instructor” who improved the success rate of suicide pacts.

Two years ago, Hu Xiaotian turned 20. In the period since then, Hu Xiaotian had landed a girlfriend and completed a successful diet. Even though it wasn’t smooth-sailing career-wise, he had found a general direction. If Xiaotian were still alive, Hu Ming was going to help him set up his own business.

Hu Ming thought his son was a completely carefree young man. But in Hu Xiaotian’s QQ universe, Hu Ming found anxiety and sadness, which his son never revealed to his father. Nearly every comment Hu Xiaotian posted involved his girlfriend—how much he missed her, the level of anxiety and powerlessness he felt over not being able to provide her a better life.

Maybe Xiaotian had sent him signals too, only he was already a big boy, unlikely to run to his father crying for help like he did in the past.

Infiltration, Intervention

Hu Ming started doing some soul-searching. When he first joined his son’s suicide chat group, he sent out five or six cash gifts, inviting members to share their thoughts on their parents and family.

The founder of the chat group, “CrayCray,” was a typical member. He was 18 and hated his parents. He was planning on taking his own life on his next birthday. CrayCray had founded several suicide chat groups, claiming that he wanted to help people who were suicidal along their way. Hu Ming had tried to change CrayCray’s line of thought on several occasions, only to find himself berated and persecuted.

The negative comments that popped up in his son’s suicide chat group every day overwhelmed Hu Ming. Several days after joining the group, he invited about a dozen of his fellow soccer fans to join, in an attempt to change the tone of the conversation. He also kept posting food and scenery pictures and shared inspirational quotes. As a result, he was expelled from the group several times.

Hu Ming had never posted a single status update on QQ, yet he soon realized that his profile attracted quite a few visitors. He started adding these strangers as friends and initiating conversations.

“Hello! How can I help?” he typed repeatedly.

As far as Hu Ming was concerned, these profile views were the equivalent of pleas for help. He was terrified of missing the chance to save a life.

Besides trying to change the minds of the chat group members, Hu Ming and his fellow soccer fans also intervened by calling the police. On July 9, Hu Ming and his friends chatted online with three suicidal youngsters from [the central Chinese province of] Hunan through the night, from late evening until 8 a.m.

One of the youngsters posted his mobile number in the group. Hu Ming immediately called the police. Hunan police were able to locate the three by tracking the number and prevented them from acting.

Another similar incident occurred in the city of Datong in Shanxi Province. Acting on a tip from Hu Ming, one of his fellow soccer fans who lived in Datong called local police. Shanxi police tracked down two suicidal youngsters in 20 minutes or so.

Soon Hu Ming became a celebrity in suicide chat groups. He became the subject of both gratitude and hatred. Chat group members all knew of a pro-life father surnamed Hu who handed out cash gifts. Over time, Hu Ming’s tab came out to nearly 5,000 yuan (around $720). Hu Ming’s also gained a reputation for reporting suicidal members and even entire chat groups to police, which drew the ire of some members. They called him a selfish and heartless subversive.

Hu Ming reported suicide chat groups to Beijing and Shenzhen police several times over the span of a month. About a dozen such groups were shut down. Yet they resurfaced despite the crackdown and the new groups drew fresh members quickly.

These elusive groups resembled a never-ending sprawl of wild weeds, fueled by a collective determination to die that drew from all corners of the country.

Still, Hu Ming remained undeterred. Over time, he added 50-plus new friends on QQ, often chatting with them until the early hours of the morning or even overnight. Every time he told his story of losing his son, it triggered memories of Xiaotian. Yet Hu Ming went through the cycle repeatedly as he tried to talk down dozens of suicidal QQ users through the night.

Hu Ming said he didn’t dare blink when he showered and couldn’t sleep with the lights out. Every day come dusk, Hu Ming started having visions of Xiaotian lying in the morgue and trying to rouse him, to no avail.

Hu Ming tried to quit and move on, but he kept feeling he had unfinished business. So he soldiered on behind his wife’s back, typing away on his laptop on their living room couch night after night with his headset on.

Pro-life Comrade

Luckily, Hu Ming wasn’t alone. In mid-July, another pro-life counselor who operated in suicide chat groups reached out to him.

Twenty-year old Li Junhua joined a suicide chat group in May. He had recently dropped out of medical school after losing some 1.3 million yuan in online gambling. A few fellow punters asked him if he wanted to form a suicide pact.

After joining the chat group, Li Junhua realized that everyone in the group went through their share of hardship, be it major debt, cancer, family breakups or failed relationships. The group members vented and complained non-stop, as if they had finally found an outlet to air all the grievances weighing them down.

Xiaoyuan stood out among these death-seekers. She wasn’t sick, no disaster had struck, nor did she have any relationship problems—and yet she was desperate to die.

Li Junhua was baffled as to what possibly could be bothering her, so he started chatting with Xiaoyuan.

On the sixth day of the Lunar New Year, Xiaoyuan flew to Yunnan Province [in the southwest of China] armed with several thousand yuan in cash after leaving her home in [the southern Chinese province of] Guangdong.

She landed two jobs in Yunnan, but neither panned out. In mid-May, Xiaoyuan, who was working front desk at a local hotel, was detained by police after she accidentally injured her boss with a broken glass during a dispute.

Soon after being released, Xiaoyuan, who was down to her last savings, started contemplating suicide. She picked a few leaves from a poisonous plant in a local park and stuffed them into some buns she bought. She had diarrhea for a day but survived.

As her savings dwindled, Xiaoyuan joined a suicide chat group, hoping to successfully die before becoming homeless. She was on a mission and terrified at the same time. She formed a suicide pact with several fellow chat group members, but their attempt failed as well.

When it came to the topic of death, Xiaoyuan’s tone was peaceful, even playful, which spooked Li Junhua. The way this young woman spoke about life completely trivialized it, contrary to what he himself was taught as a child. But Li Junhua had a hunch that Xiaoyuan didn’t have the guts to kill herself, so he wanted to meet her. He pretended to be seeking a suicide pact and made plans to meet Xiaoyuan in Nanchang [the capital of Jiangxi Province in eastern China] to carry out their deed. He transferred her the funds to cover her air fare.

On the evening of May 27, Li Junhua picked Xiaoyuan up from the airport in Nanchang. She carried a paper bag in one hand, which contained her wallet, phone and charger, and a slightly dirty pink bear in the other. Li Junhua recalled that Xiaoyuan looked quite pale and skinny that night, “as if she couldn’t afford to eat.”

Li Junhua brought Xiaoyuan to the county seat where he lived. During the two-hour drive, Xiaoyuan never stopped talking. During Xiaoyuan’s three-day stay, Li Junhua would work during the day and chat with Xiaoyuan over dinner in the evenings. Neither broached the subject of suicide. After Xiaoyuan left, she found a job in Nanchang. She had told Li Junhua earlier that she had bought a ticket to a local botanical garden before flying out to Nanchang. Her original plan was to find the most toxic plant in the garden and ingest it.

Li Junhua had saved Xiaoyuan in the nick of time.

By early June, word had spread of Li Junhua’s gambling debt. His family members started finding out one by one. He felt as if “he had been thoroughly skinned.” He could no longer cope with the pressure and felt suicidal.

He fled to the beach resort city Sanya on southern Hainan Island. Li Junhua grew up in a mountainous town near Nanchang in landlocked Jiangxi Province and longed for blue ocean.

He said that if he were to die, he had to die “in the bosom of the sea.”

After arriving in Sanya, Li Junhua relaxed instantly, now that he no longer had to face his family. He started feeling less suicidal. Half a month into his stay, he became friends with Xiaole, a fellow suicide chat group member also saddled with a big gambling debt.

“I’m still alive even though I owe 1.3 million yuan,” Li Junhua recalled thinking at the time. “He only owes some 30,000 yuan.” He was confident he could talk down Xiaole.

He pretended that he was forming a suicide pact again and lured Xiaole to Sanya. He had long conversations with Xiaole and took him for walks. He told Xiaole that death wouldn’t solve anything, that after his death, debt collectors would track down his family and hold them accountable. Li Junhua himself had an epiphany in Sanya, that if he died, he wouldn’t be able to hold on to anything.

Li Junhua didn’t want to jeopardize his own family. During his stay in Sanya, his parents cleared most of his debt. He could manage the remaining 300,000 yuan or so as long as stayed alive. He wanted to make money, so his parents could enjoy life. Li Junhua shared all these details with Xiaole. Xiaole eventually opened up to his family and his mother paid off his debts. He also started working again.

These experiences made Li Junhua realize that pro-life counselors played a crucial role in suicide chat groups. In July, he read about Hu Xiaotian’s suicide and Hu Ming’s follow-up in the news. He reached out to Hu Ming and began sharing information. He wanted a partner in his battle to preserve life.

Momentary Lapse

People who formed suicide pacts typically had run into life challenges, but they weren’t at the point of no return, Hu Ming realized. Most of the members of suicide chat groups had either relationship, illness-related or money issues, he concluded from experience. Thoughts of self-harm were magnified by their depression.

Zhang Kai from the Hunan city of Hengyang said he was hesitant before he tried to commit suicide. Zhang Kai is 19 and originally hails from a rural village. He quit school to work at a young age to boost his family income. When he was 15, he started learning about e-commerce and soon began to earn a decent income. But he eventually became an online gambling addict and lost some 200,000 yuan of his savings. His girlfriend of a year or so broke up with him over his losses.

On July 24, when Zhang Kai was at rock bottom, he accidentally discovered a suicide chat group while researching ways to kill himself. Soon Zhang Kai forged a suicide pact with fellow chat group member Ding Qiang. The next day Ding Qiang traveled from Wuhan to Hengyang. Twenty-six-year-old Ding Qiang was the same age as Zhang Kai’s older brother. Before they proceeded with the suicide attempt, Ding Qiang tried to talk Zhang Kai out of it.

But Zhang Kai still wanted to die. So the two men went ahead with their plan, which was to burn charcoal in a motel room. About an hour later, Zhang Kai, who was the more physically vulnerable of the two, passed out first. Later Zhang Kai recalled that he was in intense pain during the hour before he lost consciousness.

Ding Qiang couldn’t stand watching Zhang Kai die, so he dragged him out of the motel room quickly. It took Zhang Kai nearly 20 minutes to wake up. When he regained consciousness, he felt like his head was about to explode and couldn’t walk. After narrowly avoiding death, Zhang Kai checked his phone and saw a message from Hu Ming. He responded that he was still alive.

Ding Qiang left and never got back in touch. The chat group members traveled on different life trajectories that only intersected because of their suicide pacts. On some occasions, these encounters spelled the end of their lives. On other ones they were an opportunity for rebirth.

Zhang Kai didn’t want to die anymore. By Li Junhua’s account, many chat group members give up suicide after a first failed attempt. In his eyes, these were the lucky ones. After cheating death once, they figured out how they wanted to live their lives.

A woman walks along the grassy banks of a river in Wuhan, central China on Nov. 4, 2018. Source: ImagineChina.

But the third time Li Junhua convinced a fellow chat group member to meet in person, it was a failed intervention. In early July, Li Junhua met up with “DeepSeaFish” at a milk tea shop in Haikou [also in Hainan]. When Li Junhua arrived, sitting next to DeepSeaFish was a young woman who only identified herself as “K.”

DeepSeaFish was a tall man and had a huge rose tattooed to one of his calves. “If he didn’t speak, you never would have guessed he was severely depressed,” Li Junhua recalled. K had short hair and pale skin, but her eyes gleamed.

Li Junhua knew the couple had formed a pact to kill themselves in Haikou. The day they met, the trio had milk tea, played video games and watched “Jurassic Park.” They even had drinks and a late-night snack. Looking back on the day, Li Junhua still felt they had a great time. During the late-night meal, DeepSeaFish toasted Li Junhua, saying casually:

You don’t have to wish me anything. Just wish me an early death.

It was the only time during the whole day the topic of death came up.

The next day, the trio went their separate ways. K stopped responding to Li Junhua’s messages, but she posted a short video on QQ of herself walking.

Li Junhua had a hunch something went down. On July 19, he got word from his chat group that DeepSeaFish and K leapt to their deaths from a five-star hotel in Haikou.

The couple’s deaths were a mere pebble that caused only a slight ripple in the dark river that was the suicide chat group. Soon enough the pebble sank to the bottom of the river and no one cared.

Determined to Leave

August arrived. Hu Ming and Li Junhua still regularly received messages about deaths.

Two months previously, Hu Xiaotian was cremated in Wuhan. Hu Ming couldn’t bear bringing his ashes home. He bought a grave plot in his hometown of Huanggang in Hubei province. Hu Ming burned a portrait of Xiaotian in front of the grave. Back in Gu’an, where the Hus currently reside, Hu Ming quickly burned Xiaotian’s belongings and moved to a new apartment.

The Hus’ new apartment also has three rooms and a living room. Hu Ming has reserved a room for Xiaotian. Hu Ming and his wife lied to their younger son, who’s in high school, and their parents about Xiaotian’s death. When their parents asked, Hu Ming would say vaguely that Xiaotian was out having fun. When the elders kept pestering him about Xiaotian’s whereabouts, he said that Xiaotian might be trapped in a pyramid scheme.

“Telling them that he’s missing is better than saying he’s dead,” Hu Ming said. Hu Ming didn’t mind accepting reality himself, but he was afraid of hurting his family. The non-stop redemption mission left Hu Ming drained physically and mentally. The constant talk of life and death in the chat groups were a giant rock that weighed on Hu Ming. He kept reliving Xiaotian’s death over and over again—it was impossible to shake the grief. And eventually Hu Ming started being blacklisted by the founders of suicide chat groups. He was often banned from newly formed groups.

New members joined the suicide chat groups every day. When these newbies proclaimed their desire to die, Hu Ming treated them as real people, despite their virtual surroundings, and invested genuine emotion. Every time he failed to talk someone down, he felt devastated and defeated. Because he lacked professional experience dealing with suicidal internet users, Hu Ming always used his grief over his son’s death as a stepping stone. Yet this wasn’t a foolproof approach.

During one such exchange, chat group member “RoyallyHappy” was fiercely determined to die by suicide and indicated his deep-seated resentment toward his family and parents. Towards the end of their conversation, RoyallyHappy became very impatient and even hostile toward Hu Ming’s reasoning. It was another failed attempt.

Tong Yongsheng, the chief psychiatrist at the personal crisis research and prevention division of Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, says that the few pro-life advocates that operate in suicide chat groups often underestimate the difficulty of the task and lack professional knowledge. That, coupled with their own emotional wounds from the death of their loved ones, makes them especially prone to a severe sense of loss after failed persuasion attempts. Tong believes that suicide prevention is something the community-at-large needs to work on and not the job of lone activists.

Lawyer Zhang Xiaoling, who specializes in public interest lawsuits for teenage internet users, believes that QQ operator Tencent has a regulatory role to play.

He Xin, a security expert at Tencent, said that the company already blocks searches for phrases like “suicide” and “self-harm” on QQ. He added that suicide chat groups are shut down if verified as such after they’re reported to system administrators. A search for “suicide” on QQ’s search engine automatically generates pop-up messages that list resources for people in need of counseling.

But countermeasures like that are still contingent on suicidal internet users being proactive about asking for help. Zhu Tingshao, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Science’s Institute of Psychology, launched an automated self-help program for internet users in April 2017. The program screens Weibo posts for content suggesting suicidal thoughts and generates messages to users suggesting they seek help, with volunteers following up on the cases proactively. But the program is hampered by technical and manpower constraints and limited funding, only reaching a fraction of vulnerable internet users.

In early August, a burnt-out Hu Ming decided to bid farewell to the suicide chat groups. His younger son was about to become a high school senior and he didn’t want his mood to affect his family. He asked CrayCray to relay to other group members that he was done meddling with suicide attempts and to ask everyone to live on bravely.

Meanwhile, Li Junhua was also feeling overwhelmed. In August, he passed his army physical and was scheduled to formally join in mid-September. He too, will be forced to take a break from the suicide chat groups because he will be denied access to his mobile phone during his military service. Li Junhua hopes that one day he can become someone of influence and shine the spotlight on the issue of suicide in a more effective way, unlike his futile efforts of late.

On the afternoon of Aug. 17, Hu Ming received a suicide note in his QQ inbox. He called the police behind his wife’s back one last time. That night Li Junhua got a message from K’s mother. He bought 40 yuan worth of fake bills and burned them while calling out “Qiqi,” K’s nickname, saying:

She’s so far away. If I don’t call her name, she won’t receive the money.

In the dark corners of the internet where light fails to reach, the profile pics of suicide chat group members are quickly forgotten after they go dark. Here death is a trivial matter that makes as much noise as a feather. When life is lost, there are no songs of mourning or funerals. No one takes note.

Meanwhile, the souls they failed to save weigh as heavily as mountains on the hearts of pro-life counselors. They can’t help but look back and wonder as they stumble forward in their own life journeys.

* Some names have been changed to protect the identities of those involved.

This story originally appeared in The Paper (Pengpai), a leading Chinese news platform based in Shanghai.

Translator: Min Lee

If you enjoy this newsletter and would like to help us spread in-depth, personal stories about China, please share with family, friends, or colleagues. The sign-up page can be found here.

Until next time!