Greetings from Chinarrative.

In this issue, we feature a short, first-person narrative as told to Huang Chenkuang, a writer who compiles the “Beijing Lights” column for the Beijing-based arts collective Spittoon. Also known as Kuang, she profiles ordinary Chinese people whose life stories rarely are given the textured coverage they deserve.

Notes from Huang on her interviewee:

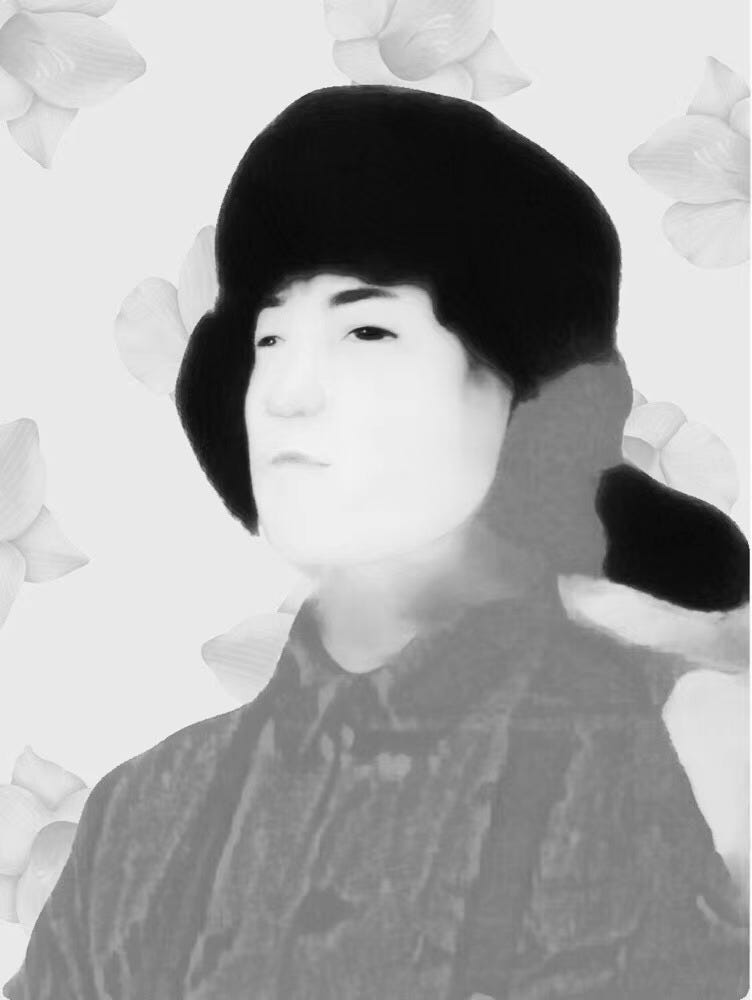

I met Zhou Lizhan* in front of his compound entrance where he sold some vintage items. He has a medium height, thin, with his hair combed backward, looking younger than his real age in his light color V-neck shirt. His grey goat and locked eyebrows add an air of stubbornness to him.

Delighted to see the interest I showed in his possessions, he invited me over to his house to check out more of his collection. The living room was full of old-style wooden furniture, leaving only a narrow path to the bedroom. There, the four walls are stacked with all kinds of vintage items, as well as several framed black-and-white photos of him as a youth in the army.

Thanks for your continued support of Chinarrative. To become a paid subscriber just click through the “Subscribe now” button below—it’s $5 per month or $50 per year. Founding member slots are also still available! Past issues are archived here.

Contact us at editors@chinarrative.com for thoughts, story ideas, or to chat about original submissions.

They Tore My China Dream Down

By Huang Chenkuang

Zhou Lizhan, male, 69, Beijinger, retired worker

People of my generation have never had it easy. We have witnessed so much history—the Three-Anti and Five-Anti campaigns, the start of joint state-private ownership, the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution.

Those who have never suffered from starvation wouldn’t know how it feels. During the three years of the Great Famine, it was said that tens of millions of people starved to death in Henan province alone. People were so desperate for food that they ate tree bark. It was the same in Beijing.

The Great Famine was partly due to natural causes, but it was more of a man-made disaster. During the Great Leap Forward, the local government claimed that 8,500 kilograms of grains could be reaped out of one mu (666.7 square meters) of land. That was just nonsense. But since they reported that number to the higher-level government, they had to submit that amount of grain. To make up the difference, they forcibly took the grain from the populace. People had no other choice but starve.

There were six kids in my family. My parents stored the flour in a dou container and carefully rationed how much we used each day. Before leaving the house, they’d smooth the surface of the flour and write words on it to prevent the kids from stealing it.

One day, I was so hungry that I couldn’t take it anymore. I furtively grabbed a handful of flour and cooked it on the stove. I hid the food until I had walked all the way to Xibianmen, then I swallowed it up in two seconds. I remember that scene to this day. My heart still feels that nameless grief whenever I recall it.

I later served in the army, taking charge of the electrical supply system. After six years, I transferred to work as an electrician in a company. I didn’t feel comfortable there since most of my co-workers were from families with influential backgrounds. I left to work in a public transport company and stayed in that job until retirement.

I don’t have many vices—I don’t drink or smoke. But I’m obsessed with vintage objects, especially wooden objects. I would give my salary to my wife every month, but leave a small sum for myself to buy old objects with. I mostly collect in the surroundings of Beijing, but sometimes in other places all over China.

My wife doesn’t object to my hobby, but she isn’t very supportive, either. She’d complain from time to time that I bring “trash” home. What looks like a diamond to you could look like a grain of sand to someone else; I get it.

Over the years, my collection has grown. My dream was to open a shop where I can display and sell these antiques and meet people who share my interests. By communicating with them, I can learn new things.

We had an apartment at the North Fourth Ring, but we sold it and moved to help take care of my granddaughter, who is in primary school. When I bought this house, one of the rooms faced the street, and it came with a business license. As soon as we moved in, I renovated it into a shop.

It felt like my dream was finally within reach, but the good times didn’t last long. Not even two years later, the government suddenly demanded that we close the shop. A team of workers came to demolish it. I showed them the business license that was valid until 2028, but that piece of paper changed nothing. If the government wants to demolish something, you can’t reason with them.

The government likes to keep up appearances, and they considered small shops to be eyesores on the landscape of Beijing. In six months, they ordered all the small shops along the street near Heping Jiayuan to be closed. All over Beijing, they shut down about 1 million shops, the livelihood of a million households.

The small park near my apartment used to be full of life during the weekend, with all kinds of small vendors. Now everything is banned. I often sit in the house, my eyes on those antique objects, and think to myself: I’m nearly 70. I will probably never have the chance to realize my dream again.

Life is so short. My youth feels like it was just yesterday. And I’m now in the twilight of my life, regretting the things I haven’t done.

Our generation has never lived for ourselves. Our whole life was about sacrifice, first for the country and then for the family. When I finally had time for something I truly enjoy doing, my “Chinese Dream” was smashed by the very people who’d encouraged me to dream one.

Edited by Hatty Liu

* Zhou’s name has been modified to protect his identity.

Contributing Chinarrative Editor: Isabel Wang