Greetings from Chinarrative.

Bringing home a paycheck or striving for career success is probably how most Chinese men show love for their families. But what happens when a father decides to give up working to focus on child care instead?

In this issue we meet Chen Hualiang, a stay-at-home dad who gets a monthly salary of 20,000 yuan (around $2,800) from his wife. He takes his parenting duties seriously and finds that he can do just as good of a job as stay-at-home moms. In doing so, Chen is also challenging gender roles in China.

The piece originally appeared on Chinese nonfiction platform Renwu. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Past issues are archived here. Check out our website. Thoughts, story ideas? We can be reached at editors@chinarrative.com.

Dear, I’m Out of Cash Again: Life and Struggles of a Stay-at-Home Dad

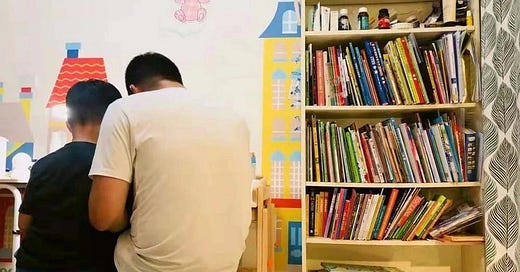

Courtesy: Interviewee

By Tu Yuqing

By the time Chen Hualiang first realized the difficulties of being a stay-at-home parent, he was already two months into the job. His wife Maoli gave a 20,000 yuan ($2,800) allowance each month, and still it had disappeared in the blink of an eye.

That was a considerable sum, compared to most salaries. In the Japanese drama “The Full-Time Wife Escapist,” the male protagonist was so wrapped up in work that he had no time for housework, so the female protagonist proposed a “contract marriage,” where she would take on the job of stay-at-home wife. They decided on an annual salary equal to 197,000 yuan, after adjusting for currency conversion in 2016. Maoli, Chen Hualiang’s wife and a successful author, paid him slighter more than that.

However, the biggest issue was that Hualiang’s salary also needed to cover household-related expenses. Cooking necessities were expensive, not to mention their weekly grocery haul. His money also had to go toward replacing scratchy towels, buying more toothpaste, and even installing a new water purifier. Living in Shanghai meant that those costs were only basic expenses.

On the tenth of that month, he initiated salary negotiations with his manager-wife. Hualiang sat in the passenger seat, looking dejected as Maoli drove. Awkwardly, he started: “So … it looks like I’ll need a bit more money.”

In disbelief, she asked: “What happened to the 20,000 yuan? Did you buy 200 pairs of pants?”

He thoughtfully handed his wife a bottle of water. Then he told her that he was just realizing the high costs of running a household, now that he was staying at home:

Do you realize how sad your standard of living used to be?

That night, he cooked Australian Wagyu beef—worth 100 yuan—for his wife, who reluctantly gave him more money and told him to spend it more carefully.

But the truth was that she had still underestimated his spending ability. Hualiang had been a stay-at-home dad for over a year now, and he still struggled to keep his expenses under 20,000 yuan. For more than half the month, he didn't have enough money to make ends meet. To stave off his wife’s worries, he would use his credit card to cover any remaining expenses. She would discreetly probe around, wondering if his allowance had stretched through the end.

Hualiang always came prepared to face his wife’s questions. Halfway through the month, he would calculate his own finances and his credit card debt before calculating the rest of his salary. Then he would casually warn her: “It’s not enough. I’ll show you the bills at the end of the month when I get a chance.”

When it really came time to look at the bills, Maoli’s questions inevitably grew more frenzied and louder: “That much?!” It was now a familiar scene to them. When she said that, it was Hualiang’s cue to list a couple of their bigger purchases that month, along with some of their frequent expenses. That usually ended their discussions, but sometimes, Maoli would persist. “Is that it then?” she asked. “That only adds up to a couple thousand. What about the remaining 15,000 yuan?” At that, Hualiang would hastily pull out his phone and reassure his wife that the money was still there—all she had to do was look at the detailed receipts.

Courtesy: Interviewee. Managing the family budget.

Spending Money

It wasn’t entirely Hualiang’s fault. Part of his expenses had to cover household expenses, and his son’s classes came with a considerable price tag: he had basketball practice, music class, and online and offline English classes every week. For a while, Hualiang had also enrolled his son, Aiwen, in golf classes to foster his “youth talent.” He asked Maoli for 20,000 yuan and signed Aiwen up for classes that cost 2,000 yuan per session. Aiwen managed to master a golf club swing.

Then there was the matter of Aiwen’s books, toy models and protective gear for outdoor activities—all of that cost money too.

Hualiang estimates that his own expenses only account for a third of his salary, at most. His clothes were purchased on sale in bulk, stuffed away at home or returned if they didn’t fit. He only ever purchased Uniqlo. But while he could save a little with clothes, doing the same with food was much harder. Hualiang relished seasonal fruits, so much that he could put away 1.5 kilos of bayberries or 1 kilo of cherries. Judging by his behavior, the only way to enjoy fruit was to eat it quickly at the peak of its ripeness. They spent about 1,000 yuan each month on fruit alone.

Hualiang seized upon a new hobby after becoming a stay-at-home father: cooking. Their kitchen was stocked with novel appliances and kitchenware, like a corn stripper for removing corn from the cob, a variety of knives for paring fruit, or baskets for washing vegetables. “I think he goes a little crazy with his shopping. Looking at some of that stuff, I don’t know why he has to buy so much,” Maoli said, thinking about the nearly two dozen spices that peppered their kitchen counter.

Their food and kitchen knickknacks didn’t amount to much, but Hualiang’s other hobby—photography—commanded a price tag that was hard for his own salary to cover. One day, he saw a drone for 10,000 yuan and decided to ask his wife for funding. He prepped her by broaching the topic with her in advance. Later, at the opportune moment, he suggested, “Maybe we should get one too.” She gave her assent, and just like that, Hualiang got his drone without spending a single penny.

His nascent line of work and the absence of industry standards allowed Hualiang to live more freely—and still collect compensation for purchases large and small. He was happy with his new boss, saying:

She’ll let me off the hook even if I spend too much.

As the boss, Maoli largely tolerated her husband’s photography hobby, aside from grumbling here and there. She was never stingy in reimbursing Hualiang, even if the tally on his month-end bills staggered her. “Giving your money to someone else to spend is completely different than spending it on yourself,” she said.

Becoming a full-time dad seemed like a sensible choice at the time. Hualiang vaguely remembers the way he decisively submitted his resignation letter in late 2017 after he decided to stay at home and raise his son. In the letter, he had attributed the cause of his resignation to “changes in [my] family’s plans.”

Incredulous, the chairman said to him:

Men should prioritize their careers. You should reconsider.

But Hualiang’s manager, whose family was in Korea, understood.

Hualiang’s first job was in Fujian, working in sales for the environmental protection industry. He only went home once a month. After his son was born, he struggled to find a suitable job in Shanghai and went to Hangzhou instead. It was relatively closer to his family, although he could still only see them on weekends.

One winter night in 2017, just after Christmas had passed, Hualiang finally had a chance to see his family in Shanghai again. Over the course of the year, he had spent close to 300 days traveling for work and he was drained. Suddenly an idea struck him. “What if I stayed at home to raise our son?” he recalled saying.

Maoli was working on the computer at the time and, trying to quell her excitement, replied: “That could work.”

The idea had been on her mind for a while, but she never thought that Hualiang would be the first to vocalize it. “You really could, you know,” Maoli instantly said as she began laying out the feasibility of the plan. That year, one of her books had sold more than a million copies. Based on Hualiang’s annual salary of 300,000 yuan, Maoli’s book sales would be more than enough to cover them for at least three years.

In the four years since their son was born, Maoli found that she didn’t have the temperament for full-time parenting. If it wasn’t her own child, she might’ve quit a long time ago. “I really am impatient,” she said. She and Hualiang had previously talked about one of them becoming a full-time parent if the other one “made it.” At the time, though, she thought she was going to be the one ending up at home.

Hualiang readily accepted. He enjoyed spending time with his kid, and he relished the children’s games they played. He was also open about his new status as a full-time parent. Whenever his coworkers asked, he always confirmed that yes, he had left his job to be with his kids. Most of his peers regarded him with envy and doubt but left it at that.

Parent Pressure

The only real pressure came from their own parents, who couldn’t understand their decision. The first was Maoli’s mother. She lived with them, and originally, her responsibility was raising her grandson Aiwen. Now that Hualiang would be parenting, she was all but out of a job.

In the beginning, Hualiang didn’t even tell his own father about his new arrangements. He had been on his own since middle school, down to making many important life decisions. He rarely consulted with his family and this was no exception. One day, his father called him to catch up with him. Only then did Hualiang tell him that he had decided to stay at home.

Even from thousands of kilometers away, Hualiang could sense his father’s disappointment. His father was more conservative, after all. After a long pause, he finally asked, “Can’t your wife do that?” Hualiang had never expected him to understand their decision, but that question still irked him. Raising his child and being a full-time dad was still a proper job, even if his father clearly thought otherwise.

But the “aunties” in their neighborhood continued to give them grief. They disdained that a man like Hualiang had given up his job for his family and thought that he had no future prospects. They also doubted his parenting abilities. The spectacle of Hualiang teaching his son Aiwen to bike nearly frightened them to death. At one point, Hualiang said he was letting go of the handlebars—and then he did. When they saw, they shrieked that Aiwen was falling. Keeping his head high and his face composed, Hualiang replied: “Let it be. He’ll stand up on his own.”

He wasn’t really being neglectful. He had dressed Aiwen in full-body protective gear that he had gotten online, so even if Aiwen fell, it wouldn’t have caused any real injuries. Still, the aunties gave him no peace. One of them even told Maoli:

Of course kids would want their father to parent them. Men are more heartless. Your son tumbled headfirst into the lawn and he just stood here, watching.

Hearing that, Maoli and her mother grew so alarmed that they rushed over to find Aiwen.

But the consequence of that ordeal was that Aiwen mastered biking a few days later. Proud of their achievement, Hualiang let Aiwen ride his bike all around their neighborhood as a demonstration of his teaching success—and to make sure that every single auntie saw.

Soon afterward, Hualiang upgraded Aiwen’s bike to a larger model, which ate into his monthly salary. His love of shopping had only grown since he became a full-time dad, and he made purchases online on Taobao nearly every day. Every morning, after he had sent Aiwen to school, the delivery couriers would start making the rounds to his home. Their knocking regularly disrupted Maoli, who worked from home. On one occasion, she collected 17 packages for her husband in a single day. That made her realize that if a woman is looking at her partner’s phone, it isn’t necessarily to see if he was talking another woman—it could just be because she’s trying to monitor all his online shopping.

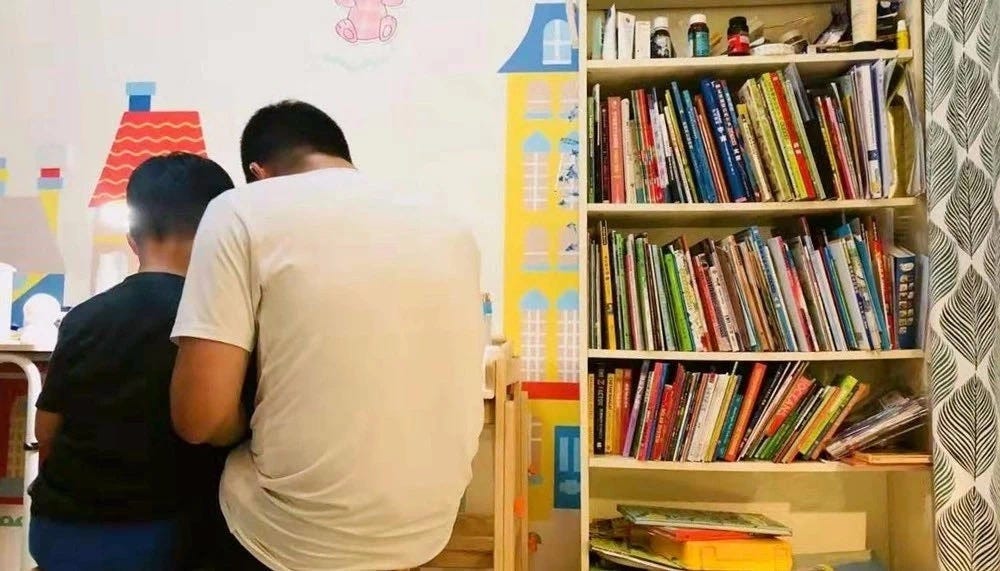

Courtesy: Interviewee

There was another important reason why Hualiang was willing to swap roles with Maoli. When their son Aiwen was five, one year away from entering elementary school, neither parent had expected such stiff competition for getting into a good school. They had started preparing a year ago, but that just meant they were already behind the majority of Shanghai families. After all, many schools started interviews six months in advance, so Hualiang and Maoli only had the latter half of the year to make some decisions: would it be a public, private, or international bilingual school? Should they buy a house in the schooling district they wanted, or should they gamble on testing into it? These are issues almost every parents face.

Despite the difficulties, Hualiang, who had just stepped into his new parenting role, remained confident. He registered Aiwen for interviews at 20 private schools, marking the start of his arduous training to get into elementary school. The class fees were naturally exorbitant and amounted to at least 50,000 yuan over six months, according to Hualiang’s calculations.

Most training institutions promoted their class bundles as the cheaper option, with bundles split by time and length. For instance, parents could choose classes with a set number of sessions (20, 40, or 80) or a set length (three months, one semester, or one year). After careful analysis, Hualiang usually went with the middle option: it was valued just right, and it had just enough sessions for them to feasibly finish. Plus, if he had to explain to Maoli why he had chosen the middle option, then at least he could say: “If we registered in too few classes, then we’d have to buy more again when the time comes, and that would cost more.”

Then there were other expenses that became more regular. Given the weight of his schooling responsibilities, he bought Aiwen a study desk specially designed for his size, which cost more than 3,000 yuan. The better classes were located farther away, and he once drove more than 50 kilometers just bringing Aiwen to school each week. Before a week was even up, he had already used up a tank of gas, which cost another 300 yuan. When he lingered outside the classroom and waited for Aiwen to finish, he was one of the few men there.

Courtesy: Interviewee

As Aiwen’s studies suddenly picked up, the brunt of his assignments also fell on Hualiang. Everybody knows that working on homework could push even the gentlest mother to her limits; Hualiang was no exception. One night, when Aiwen was working on his math problems, Maoli heard Hualiang roar through the wall: “How much is nine plus two? HOW MUCH?!”

Maoli couldn’t sit by any longer. She dashed over to the room and rebuked Hualiang, saying:

If you have a problem, you come to me. Don’t take it out on our kid.

He snapped:

Why can’t I scold him? I just can’t help it.

Maoli felt her anger rising and said:

If you’re mad, it just means you can’t do it. If you can’t teach him well, then don’t bother teaching him at all.

Their argument grew more heated until they were yelling incoherently at each other. Then Maoli spat:

You’re not fit to be his father.

As soon as she said that, the room suddenly went still. To her surprise, Hualiang started crying, which only made Maoli cry too. In that moment, she realized: “He’s actually crying over this. He really does care about being a full-time father—he really wants to do well.”

Looking back, Hualiang attributed his crying to his feelings of guilt. He knew that yelling at Aiwen could only lead to poor outcomes, so whenever it happened, he would always apologize to his son and ask for forgiveness after he had calmed down. “I want to send a clear message to Aiwen that this sort of behavior is wrong, and if something is wrong, I want to apologize for it,” Hualiang said. “I need him to know right from wrong.” He also approached Maoli and proposed an accountability system: he would be fined 2,000 yuan each time he yelled at Aiwen.

Nine months later, Aiwen finally made it into the school of his parents’ choice. Hualiang was also able to push back against the perception that dads were unfit to parent their children. When Maoli messaged some of the other mothers with news about Aiwen’s new school, they flooded her with questions: what kind of classes did they choose for Aiwen? How much was it? How did they apply? How did they prepare reference letters? Maoli had no answers for any of the questions. She just gave an honest response, saying: “Thank goodness for Hualiang. My only job was to worry.”

Overwhelmed, Overweight

After becoming a full-time dad, Hualiang unexpectedly saw himself gain weight by the day. He had been overjoyed when he left his old job, thinking that he would now have ample time to himself, like setting aside an hour in the afternoon to go swimming.

But various household matters started chipping into Hualiang’s personal time, one at a time. He woke up at 6 a.m. each day, made Aiwen breakfast, and drove him to school at 7:30 a.m. By the time he got back home, it was nearly 9 a.m. At 3 p.m., he had to make another trip to school to get Aiwen, but they often stayed at school to work on his homework. It was nearly dinnertime by the time they reached home.

It was Hualiang’s free time from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., but he was also responsible for preparing Maoli’s lunch. Once he had finished this daily tasks, he hardly had any time left for himself. On weekends, he had to take Aiwen to his extracurricular classes. He never had a weekend off, and in the space of two months, his plans to go swimming fell from four times a week to zero.

Hualiang was in a WeChat group with other full-time dads, all German dads who had moved to China for their wives’ jobs. Without a work visa, they couldn’t find jobs and decided they may as well stay at home with the kids. Hualiang met up with them once a week. When he told them about his weight gain, they looked down at their own bellies and ribbed Hualiang: “Welcome to the club.”

With pressure on all sides, Hualiang once complained to Maoli: “Can we hire an hourly helper to take on some of these tasks?” As a newcomer to the position, Hualiang aspired to some kind of promotion within this traditionally maternal industry, rather than throwing all his efforts into the minutiae of the household. He wanted time to himself and time to update his WeChat account. He was good at his job and had earned a considerable number of fans, gradually making him an internet celebrity.

Courtesy: Interviewee

Maoli wrote about Hualiang’s unique experiences over the past year in her new book, “Full-Time Dad,” but he didn’t overthink it:

I just happened to do something that most dads don’t do, but I’m lucky for it because I’ve learned so much.

Before, even when he was at home, he could never fully focus on spending time with Aiwen because he had work to do. “You’ll think that as he grows up, you’ve missed out for too long, and slowly there are more regrets and remorse. One year, two years, then three years—these feelings keep building up,” he said.

But now it was different for him.

One day near the end of November last year, Aiwen suddenly started feeling sick. Hualiang took him to the emergency room and waited three hours before the doctors saw them. He was glad that in those moments, he and Aiwen were together.

Hualiang said:

Even just being with him through these hardships, I’m satisfied.

Translator Katherine Tse is a recent MA in Translation graduate specializing in Chinese to English. She is based in the U.S.

Contributing Editor: Isabel Wang