Greetings from Chinarrative!

A migrant worker’s farewell letter to a public library in the manufacturing city of Dongguan touched millions of Chinese people recently. Fifty-four-year-old Wu Guichun, who spent the past 12 years living there, had to return to his hometown when factories were shut down due to the Covid-19. Before he left, he wrote a thank you note to the library which was then posted by a librarian and circulated widely on Chinese social media.

In this issue, we meet Wu and the people at Dongguan Library. The story originally appeared on the Chinese nonfiction platform Renwu.

Known as the factory of the world with more than 150,000 industrial enterprises, Dongguan in the southern Guangdong province hosts millions of migrant workers. Its diversified industrial ecology offered Wu and his generation of older migrant workers a place to survive. The library was also a refuge, providing Wu companionship and comfort in the sprawling factory city. As Wu wrote in his emotional parting letter:

Looking back on my life in Dongguan, the library is the best place I’ve been … I will never forget you for the rest of my life, Dongguan Library. I hope you will rise and prosper, benefit the city, and spread your wisdom to all migrant workers who come here.

Support Chinarrative:

A big thank you to those who’ve become paying subscribers. It’s been very encouraging to see your support. Thanks again. A special word of gratitude to our founding members — your $200 contributions will go a long way to making this newsletter financially sustainable.

We’ll continue to ask for reader support to help with our costs. This edition of Chinarrative cost 3,500 yuan to produce, that’s just over $500. The money went to translation and editing fees.

Based on feedback from a valued reader in Portugal, we’re simplifying the donation process by dropping the Patreon option for now. To become a paid subscriber just click through the “Subscribe now” button below — it’s $5 per month or $50 per year. Founding member slots are also still available!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Past issues are archived here. Check out our website. Thoughts, story ideas? We can be reached at editors@chinarrative.com.

Now onto the story!

A Double Life: The Avid Reader of Dongguan Library

Wu Guichun browsing books. Courtesy: Xiaoqing An / Renwu

By Xiaoqing An

It was a parrot in Dream of the Red Chamber who could recite poems that ignited Wu Guichun’s will to read when he first started coming to the library with a trusty Xinhua dictionary more than 10 years earlier:

Lin Daiyu was about to shed tears once more; but just then her parrot, which had been perched aloft under the veranda leaves, seeing that his mistress had returned, flew down with a sudden squawk that made her jump.

The parrot heaved a long sigh, uncannily like the ones that Daiyu was wont to utter, and recited, in its parrot voice:

Let others laugh flower-burial to see: Another year who will be burying me?

Wu found it incredible that one single parrot could be so powerful. If Lin Daiyu, one of the main protagonists in Dream of the Red Chamber, had a bird that could recite poems, why couldn’t he?

One July evening in 2020 at Dongguan Everbright Property Management Company’s staff dormitory, Wu Guichun let me in on the story. In 10 years, Wu Guichun had read Dream of the Red Chamber four times. The boost to his self-esteem and confidence from reading led him to memorize poems and more importantly, find a kind of balance between life on the assembly line and in the library that sustained him for 17 years in Dongguan, his “double life” in the “world’s factory.”

A month earlier, on June 24, Wu Guichun had set off to return his library card and get back his 100-yuan deposit (around $14) before returning to his hometown in Hubei province for good. On the invitation of the Dongguan librarian Wang Yanjun, he wrote a message in the visitor’s book:

I have been in Dongguan for 17 years, of which 12 have been spent happily in this library reading books. Books have feelings and do not hurt people. This year the epidemic has killed off plenty of industries and sent migrant workers packing. I have chosen to return to my hometown. All these years, the library has been my favorite place. Although I am reluctant to give up my card, life has made the decision for me. I will never forget you for the rest of my life, Dongguan Library. I hope you will rise and prosper, benefit the city, and spread your wisdom to all migrant workers who come here.

The story of Wu Guichun and the library has become one of the sweetest stories to come out of this turbulent year in Dongguan.

Back to the books: among all the books Wu has read, he likes Dream of the Red Chamber and San Yan Er Pai the most. He is a firm Daiyu fan.

“Lin Daiyu is something of a genius. They are all lonely and arrogant, talented people, from Su Dongpo to Li Bai,” Wu asks, referring to famous figures from Chinese literature.

After a drink or two, the man had loosened up somewhat and now stared in the direction of the dormitory door. Unbidden, he began reciting “Funeral Flower,” “Good Song” and “Good Song Notes” from Dream of the Red Chamber.

On finishing he declared:

This is the essence of Dream of the Red Chamber. If you haven’t engraved them on your heart, you’ve read the book for nothing.

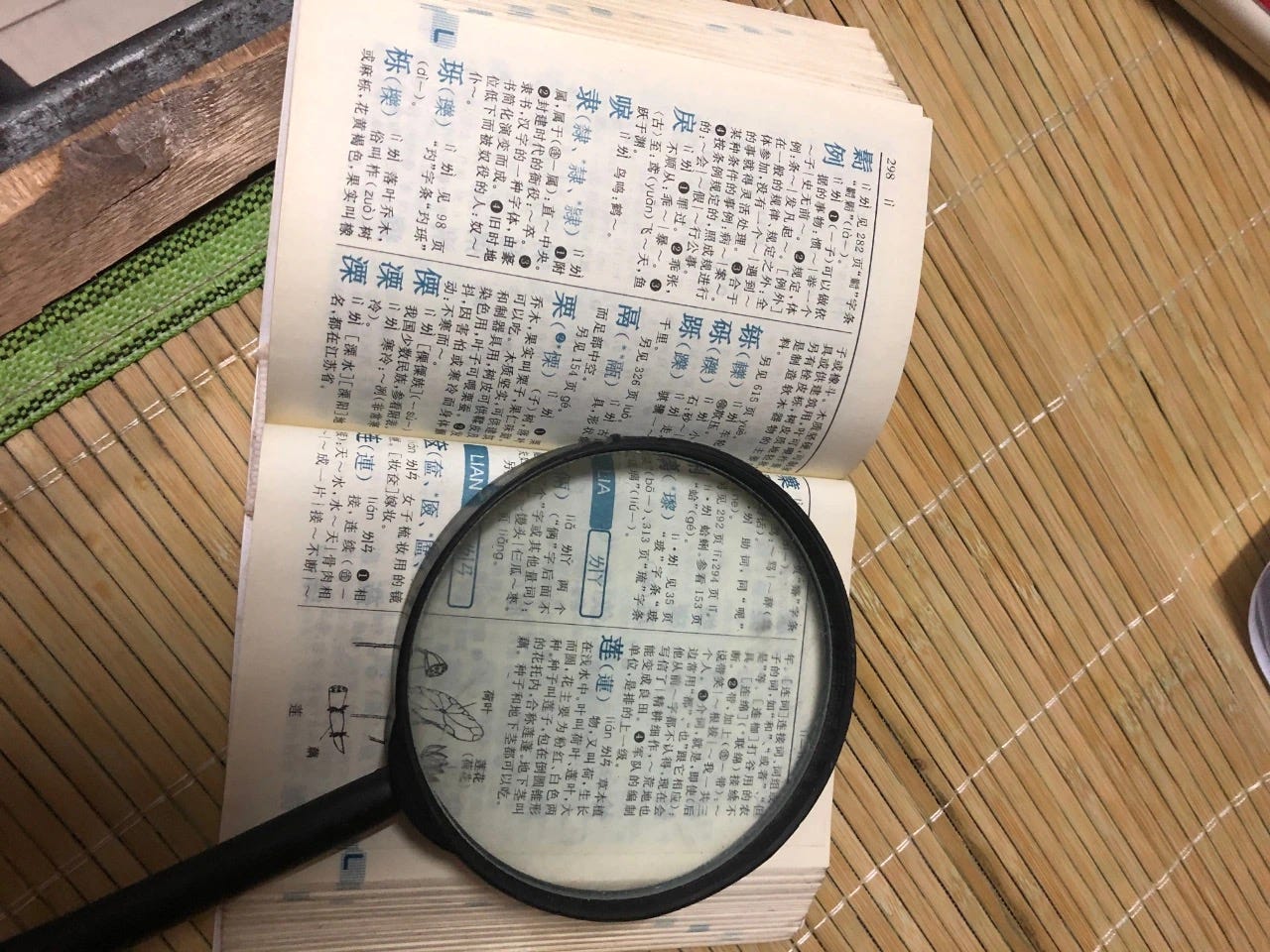

Wu’s magnifying glass and dictionary. Courtesy: Xiaoqing An / Renwu

In 2003, Wu Guichun’s father, a native of Xiaogan, Hubei, passed away. Wu Guichun’s wife had left him and he and his son faced crippling poverty. Coupled with the death of his mother earlier that year, Wu Guichun felt he had no choice but to seek work in Dongguan far to the south, and he decided to go alone.

He was 37 years old and a primary school graduate. This classed him among the least competitive workers in the industrial city. On the assembly line, people need to be strong. Older laborers like Wu Guichun could only find work in small workshops where conditions were harsher.

His first job was in an illegal factory. A month after starting and his pockets were still empty. People told him he could find better work in a factory area near to Houjie in Nancheng district. This patch of Dongguan was known as one of the “shoe capitals” of the world and was dominated by private workshops owned by people from Wenzhou (a town in eastern China known for its entrepreneurs).

The tiny ramshackle workshops were packed as densely as matchboxes. Without proper fireproofing and environmental protection, most had no need for placards out the front. Inside they were full of glue, leather and plastic soles.

Wu did odd jobs to begin with. He swept floors, moved stacks of soles around, and carted leather here and there. Finally, he learned a craft he could practice until perfect — shoe polishing.

To polish shoes, you needed two things: a glue machine and a hot air gun. The head of the glue dispenser rotates at high speed to remove excess glue and stains on the shoe, and the hot air gun burns off loose threads.

Before polishing, there are more than a dozen other processes involved in making shoes, so Wu Guichun waited around a lot. His workstation was tucked in beside towering iron shelves on which the new shoes were placed — far from the other workers.

Wu Guichun sat alone in the shadows polishing the leather shoes. When the shoes reached him, everyone else got off work. Yang Li, the shoe factory owner said Wu Guichun would spend his time waiting for work on a stool in the well-lit corridor, reading.

The shoe factory where Wu used to work. Courtesy: Xiaoqing An / Renwu

Many workers in the area are couples who come to Dongguan together. Wu Guichun came alone. In order to pay for his son’s school tuition and living expenses in middle school, university, and during postgraduate studies, he led a simple life.

He paid 180 yuan a month for rent, and for the money had the cheapest house he could find, in one of the infamous urban villages of Guangdong. It didn’t come with a toilet. The room had space for just an iron frame bed and a gas stove. A fan above the bed, a Xinhua dictionary, a magnifying glass, two books on healthy diet and prevention of hyperlipidemia, and a jar of goji berry and orange peel wine under the bed were all he had. Wu’s only freedom was that he could pack up and leave anytime he wanted.

Wu and his son had a commonly distant father-son relationship. Along with being alone for many years, the two spent very little time together. Each month Wu kept 1,000 yuan and asked the factory owner to send the rest directly to his son’s bank account. The child was boarding at school and spent the rest of the time at his grandmother’s house.

He had brothers and sisters in his Hubei hometown. After the death of his parents, their home was demolished and rebuilt. His brother and sister had older children, and when he went home, he had no place to call his own. The bed, quilt, and tableware were all theirs. They would call him for meals and he would eat.

Many times, he wanted to have someone to talk to and could find no one. He and his wife never divorced, but they have not seen each other for many years. The father of the shoe factory owner sometimes chatted with him. The old man heard him say angrily:

Living to 60 years old is plenty. No need to live longer.

The work was not technical and gave him no sense of achievement. In the off-season, there is nothing to do to make the time to pass. The workers played card games, went shopping, and had fun. He has no remaining money to play cards or buy things and was always short of money. At first, he bought a few second-hand books from the street stall to pass the time. This was then that he read Dream of the Red Chamber for the first time.

The south of China is very hot in summer, and the library is located in the administrative center of the city, surrounded by squares, parks, exhibition halls and municipal government buildings.

There are millions of migrant workers in Dongguan. “They haven’t studied much. If you give them Chinese and Western cultural comparisons or lectures on international relations, they won’t be interested,” librarian Wang Yanjun said — “Leisure” should take first place: the freedom to “come in and take a look and eventually read something.”

The very first time he went to the library, Wu Guichun was nervous. Coming up to the front gate, he had a sense of trepidation. When he had traveled south for work, “security guards meant trouble,” he said.

That day, the security man did not check his ID. No questions asked, Wu took a book from the shelf in the periodicals reading room on the third floor. He read until late and no one paid him any attention. Only then did he know for certain that this library would not charge him.

When he went for the second time, he took a pen and a notebook, wrote down the new words he didn’t know, and started looking them up in the dictionary. The shoe factory had no work in the off-season, so off he went to the library after breakfast and did not emerge until it was dark. He had no need to stop for lunch: “I wasn’t hungry. It may be that the air conditioner inside is so well adjusted. You don't move too much when reading books and don’t burn energy.”

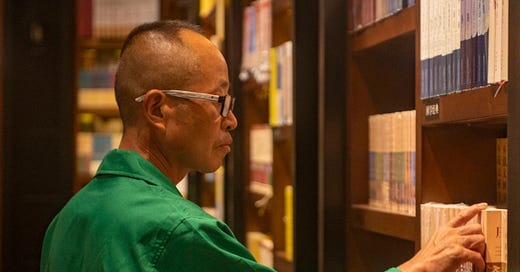

Courtesy: VCG Photo

Wang Yanjun, the staff member on duty on June 24 who invited Wu Guichun to leave a message, recalled that once, a boy was waiting at the reception desk for a new card and had asked Wu: “So many history books, all with different views. Have you ever thought about which one is true and which one is false?”

Wang remembers his reply. Wu Guichun told the kid there was no absolute truth in history:

The history one writes is all about perspective. So it depends on how much you have read and which viewpoint you are willing to take.

The avid reader liked the third-floor reading room best. On the north side, there is a red sofa by the corner with a strong frame. He said: “It’s very comfortable to snooze there for a second when you’re tired from reading.” He was sorry to lose the spot to someone else when he got to the library late. Looking out from the window behind the sofa, there were mangoes, banyan trees, magnolias and camphor trees, all common in the subtropical parts of China.

The staff in the reading room all knew him. Sometimes he would bring in biscuits or bread, and while these were prohibited, no one stopped him. His focus and dedication meant he could skirt the rules. One said: “if I disturb him, it’s me who feels uncomfortable.”

The diversified and flexible industrial ecology of Dongguan enabled Wu Guichun and his generation of older migrant workers to survive in warm southern crevices. The library was in the center of the city, like a lighthouse on the sea, offering solitary folk long-term companionship and comfort in the deserted city.

The workers went home for New Year. The off-season at the shoe factory lasts as long as 40 days, but Wu rarely took the trip. “If you go home you have to spend money,” he said.

Dongguan has a “no fireworks” policy, so the center of the city was calm throughout January 2020, and Wu Guichun went to the library every day to read as usual.

Wu lives in loneliness: “I’m used to it. It’s natural for me to pass my time by reading. And this is why I go to the library over New Year.” He reckoned that without the 40-day holiday every winter, he would never have read so many books over the past 10 years.

Before the Spring Festival holiday, Wu Guichun told the shoe factory owner Yang Li that now his son had a stable job, Wu wouldn’t need to polish shoes anymore. In the new year, he would find an easy job. He wouldn’t ask for more than 2,000 yuan a month.

The 2020 epidemic disrupted everyone’s plans. Wu Guichun, who was originally going to return to Dongguan in February to find an easy job, had to stay at his brother's house until June. Yang Li’s shoe factory could have resumed work in April at the latest, but he was still waiting for foreign orders in mid-June.

The pandemic affected every producer in the factory of the world. Compared with Spring 2019 when 70 or 80 small factories were stuffed into the industrial park where Yang Li had his workshop, this year only 20 remained.

Wu had no way to board a train to Dongguan without a letter of permission from his work unit, and as he had quit, there was no letter to be had. So, he only returned to Dongguan on June 23, two days before the Dragon Boat Festival.

The rent was due to expire on June 26. Before coming, he had called ahead to find that the shoe factory was without orders and jobs were scarce. He understood that his hope of finding another job in Dongguan was very slim.

Which takes us back to the day he handed in his library card.

Wu Guichun conceived his note for a few minutes, feeling calm. As expected, he couldn’t find a job. In the 133-character message, he wrote:

All these years, the library has been my favorite place. Although I am reluctant to give up my card, life has made the decision for me. I will never forget you for the rest of my life, Dongguan Library.

After Wu Guichun left this message, another librarian was just coming back from lunch. Hui Ting read the message and thought: “It’s just like a love letter.”

She took a photo of the message and sent it to the internal group of librarians. In the following 24 hours, through reposting on WeChat, social platforms, and the media, “A reader’s message to Dongguan Library” had become a 2020 trending topic.

Wu tends the gardens at Jinghu Garden Community. Courtesy: VCG Photo

On the morning of June 25, Wu Guichun made one last loop of the Nancheng neighborhood on his bike looking for recruitment notices. Not one job notice was to be found. He was going to have to return to his hometown.

At lunch, he pondered his fate. But then, shortly afterwards, it took a turn. He started receiving calls from Dongguan TV and Dongguan Times: “One reporter spoke to me on the phone. He said: ‘you are very popular on the internet.’ I said: “How would I know? Even if I have a mobile phone, I just use it to make calls. I don't know anything else.”

In the evening, he received a call from the local human resources and social affairs department who asked him what kind of work he preferred. Now he was famous, they planned to find him a suitable job and keep him in Dongguan. He replied that he wanted to stay in a shoe factory.

A day later, the department found him a large shoe factory in the neighborhood. But Wu didn't want to move a block farther from the library. Then Guangdong Dongguan Everbright Property Management Company approached him. The company wanted Wu to tend the gardens at Jinghu Garden Community, less than two kilometers from his favorite place. He agreed. On June 26, Wu left the rented room where he had lived for 17 years and moved into the Everbright staff dormitory.

Wu Guichun’s life had been touched by fate in a good way. And almost every person involved mentioned the same pivotal moment. If it had not been Wang Yanjun — the librarian who had keenly observed and empathized with this ordinary reader day in day out — on duty when Wu said goodbye to the library, he wouldn’t have left behind that note as he said farewell.

And this story would not have happened.

Translator: Heather Mowbray

Contributing Chinarrative editor: Isabel Wang

Good.