Happy new year from Chinarrative!

We usher in the new decade with an in-depth look at the human face of China’s booming transportation industry. Southern People Weekly reporter Huang Jian embedded himself with three truckers over the span of 10 days, crisscrossing southern and central China in an epic 2,500-kilometer journey. This is a translation of his recent report, a poignant portrait of the physical and mental toll of long-haul trucking.

Lastly, a few quick announcements. After experimenting with a variety of publication schedules last year, we will be settling down on a monthly routine of the third Friday of every month this year (China time). We will also be cleaning up our website, which will serve as a permanent and more readable home for all the stories first published in the newsletter.

New to Chinarrative? Subscribe. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Past issues can be found here. Thoughts, story ideas? We can be reached at editors@chinarrative.com.

The Fatigue and Pain of a Chinese Trucker

Illustrations by Nath. Courtesy Southern People Weekly.

By Huang Jian

Solitary Travels

The road rose before us, rugged and craggy. The palm trees behind us faded into broad-leafed trees. Our journey from Shenzhen to Hunan had gone smoothly. Zhang Yaofeng and I wove through the national and provincial highways in his Jiefang-branded semi truck. Night had fallen by the time we arrived at Qingyuan, a city in southern Guangdong Province. As we crossed into Lianzhou, we saw only mountain roads. The truck followed the winding path as it slowly passed through the steep Nanling Mountains, eventually reaching Lanshan County in central Hunan Province.

A truck driver and a journalist make for an odd pairing. After a decade in Beijing, I had moved to Guangzhou a month ago. My life had been peaceful—mind-numbingly so—and, after mulling it over for a morning, I decided that a move might inject some excitement. Just before that, a friend had breathlessly described his travels from Beijing to Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Gansu, Xinjiang, Tibet and Yunnan. What had made his experience so notable was his mode of transportation: long-haul trucks.

It’s hard to say if my friend’s story and my impulsive decision were related. All the same, I was struck by the cast of characters he had encountered, their rich experiences and their many stories. Or perhaps they themselves were the story. Long before the advent of mass media, these wanderers had provided people with news from far-flung places, but now their voices have faded in an era where people have grown accustomed to seeing the world through their devices, these very wanderers faced an uncertain future.

But things change over time. These days we must concede that we have tired of conventional approaches to journalistic storytelling. When I racked my brain for a new story idea, I suddenly saw the solution: truck drivers, the modern-day descendants of the sailors and caravans who once freely roamed the world.

More precisely, I was excited to follow truckers and experience the ancient process of story creation. China had built over 4.5 million kilometers of roads by the end of 2014, enough to circle the world more than 40 times, while 30 million truck drivers bear the burden of transporting 75 percent of China’s cargo. But they do more than drive. They eat, sleep, play cards, make love and even tangle with robbers on the road. I knew their stories would be fascinating. I had often imagined myself teaming up with a truck driver and setting off for the distant unknown. Still, my friends reminded me that they might not want a stranger tagging along, given how regularly they encounter thieves.

Then in April, a friend at a logistics company introduced me to Zhang Yaofeng, a semi driver who ran the Shenzhen-Chongqing route delivering raw materials and components for Foxconn. He was preparing for yet another trip, this time delivering shipping containers, and he agreed to take me along, if only for that friend’s sake. I met him outside the Shekou Container Terminal in Shenzhen on April 14. A light drizzle was falling. He sat with his back against the driver’s seat, legs propped against the steering wheel, and watched the TV show Youth Assemble on his phone as he waited for a call about the cargo.

The serpentine Yonglian highway connects Lianzhou, Guangdong and Yongzhou, Hunan. Known as the “Road of Death,” it coils around the mountains and forces drivers close to the edge of the precipitous cliffs. Since its completion in 1997, it has seen a number of severe car accidents. A total of 2,553 accidents and more than 170 deaths occurred in the 18-month period between October 2008 and March 2010 alone, according to the Yongzhou City traffic police. We were now driving along this very road—narrow, winding, steep and blanketed in a heavy fog. Despite having traversed this road countless times over the past decade, Zhang Yaofeng still drove slowly. By the time we passed over the Nanling Mountains, we were half an hour behind schedule.

After more than two hours, the towering mountains soon disappeared behind us, replaced by low hills. The Yonglian highway (S216 provincial highway) abruptly straightened and expanded from two lanes into four. Before long, we even started seeing rows of street lamps.

The clock on the dashboard registered midnight. A new day had started. Yawning several times in succession, Zhang Yaofeng rested his hand on his left hand, his elbow propped on the door. He kept his right hand on the wheel. I had already caught him with his eyes closed a couple times. His head would dip forward, almost crashing into the steering wheel, but then he would quickly snap back awake. Slightly worried, I would quickly ask in a loud voice if we were approaching Lanshan County and then pass him a cigarette. He shifted slightly, bringing his left hand back to the wheel and taking my cigarette with his right. “About half an hour,” he replied, inhaling deeply. He had been driving for almost 12 hours by then, stopping for only 30 minutes to eat. Driving continuously for more than four hours is classified as drowsy driving, according to transportation laws.

Zhang Yaofeng had never wanted to drive long-distance. “It’s tiring and unsafe,” he said, but he had a family to raise and, nearing 50, had no other skills. “What else could I do?”

The other drivers called him “the big guy from Henan,” a nod to his imposing physique. He was born in the 1960s in the village of Zhumadian. Zhang had a son and a daughter, but, poor as they were, he had tried farming and working in the mines. In 2006, some of his friends and family began earning money as long-haul truckers, so he decided to leave his hometown and make a living as a driver in Shenzhen. Five years later, he bought a second-hand semi with a few thousand dollars in savings and a loan. When it had to be scrapped less than two years later, he purchased another used car.

After driving for a decade or so, Zhang Yaofeng had made nearly a million yuan ($144,000). “Better than working in a factory,” he told me. A few years ago, he used his hard-earned savings to build a new home, complete with a yard, in his Henan hometown, which gave him a small sense of accomplishment.

Then his car broke down in the fall of 2015, forcing him to take out a 300,000 yuan loan from the bank. This time, though, he bought his first new car—a Jiefang semi-truck. He had to pay monthly installments of 10,000 yuan, but he figured he could repay the loan within two years.

Still, he sometimes felt like he was working for both the bank and the logistics company. Privately owned trucks are not allowed in Shenzhen, so the majority of truck drivers had to be contracted under logistic companies. Those companies also delegated their load assignments, forcing drivers to curry favor with the company leaders and dispatchers if they wanted better-paying work. At times, they also had to pay kickbacks. As much as he disliked this practice, Zhang Yaofeng had no choice but to act likewise.

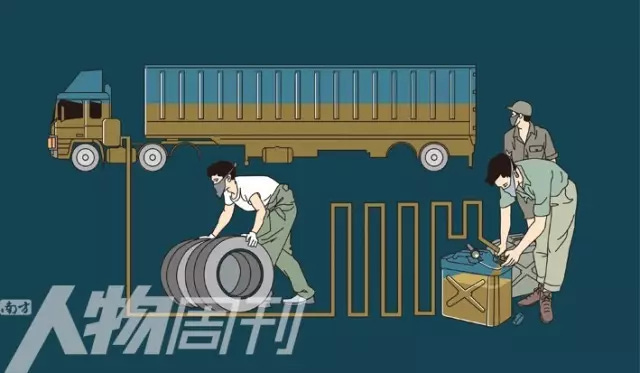

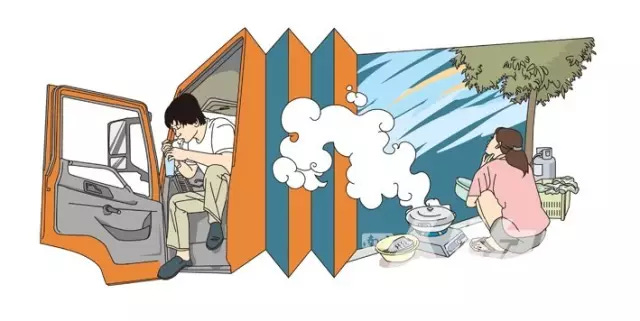

A hard worker, Zhang Yaofeng drove more than 16 hours each day. His friends were all truckers and like him, they drove the entire journey themselves, rather than switching off with relief drivers. They earned more that way—at the cost of greater exhaustion and boredom. Some drivers brought their wives with them, who would chat with them, cook for them and do their laundry. Zhang’s wife had tried to travel with him before but, unaccustomed to the lifestyle, returned home. Instead, he often relied on phone calls to pass the longest stretches of his solo travels and to help him stay awake. When I was with him, he spent most of his time talking to his trucker friends or family members on the phone.

It was idle chatter—where they would go for drinks and food after delivering the cargo or how to cook the carp his friend just caught—but enough to rack up his phone bills to 500 to 600 yuan each month.

At 12:30 a.m. on April 15, our truck finally reached the outskirts of the county seat of Lanshan, Hunan. Zhang Yaofeng topped up on gas. As we pulled out, he yawned widely again and lit another cigarette. A few minutes later, he tossed the butt out the window and started eating pumpkin seeds. He needed to keep his mouth moving, he said, or else he would fall asleep.

For long-haulers, fatigue and loneliness lurked at every turn. They turn to smoking, betel nuts, Red Bull, coffee, strong tea, and even illegal substances to combat these daily struggles.

Swerving Trucks

After passing the county seat of Lanshan, we saw a truck driving slowly along the S-curved road but swerving back and forth. The drivers behind it kept honking until it veered back into its own lane. Zhang Yaofeng hit the brakes, saying, “That usually happens when the driver is falling asleep. We’ll keep our distance and just keep honking.” Drivers called that kind of truck a “swerving booty truck.”

Exhaustion easily visits a long-hauler like Zhang Yaofeng at any time, so they fight their tiredness through different ways. Zhang relied on nonstop smoking, chewing betel nuts and eating pumpkin seeds. He said that he smokes two packs a day. Smoking remains the most popular method of staying awake. Nearly every long-haul trucker is a chain smoker.

A few days later, I met Zhang Keyuan in the southwestern city of Chongqing. A long-hauler for 17 years, he refuses to shortchange himself when it comes to smoking. He showed me the Burmese cigarettes he kept by the driver’s seat and excitedly offered some to me, saying, “Smell this.” A few months ago, while he was on an assignment to the southwestern province of Yunnan, he had purchased the cigarettes from a duty-free shop by the China-Myanmar border. He started telling me about the different kinds of cigarettes he had tried, both domestic and foreign-made, and the smoking habits of people in different regions. Cuban cigars are the best, he would say, or that people in Yunnan like smoking out of a very long bamboo pipe.

As he spoke, he lit himself a Burmese cigarette. He gestured at the deposit of yellow tar in his transparent filter, saying, “Look how much tar there is.” He had gotten an accessory specifically for filtering out tar, but at the same time, he had no plans to quit smoking. “I don’t chew betel nuts or take drugs,” he said. “I just smoke.”

Zhang Keyuan had a trucker friend who, after a couple years in the industry, found a vastly different way to stave off his exhaustion. When the fatigue hit, he would take a swig of beer or baijiu, a high-alcohol spirit. He held his alcohol well and rarely got drunk. Occasionally he would take a couple pulls from the baijiu after too many hours on the road, but that only made him sleepier. His truck would start swerving as he drove. That reminded me of The Journey, a film by Argentinian director Fernando Solanas, in which one of the drivers was forever slithering his way on the road in his truck. I had entertained the thought of riding with Zhang Keyuan’s friend, just for the thrill of it, but my fears won out in the end.

While a number of long-haulers drink, some rely on drugs to stave off exhaustion. A few months ago, a dispatcher from a logistics company told me that some of their truckers used magu, a stimulant consisting of methamphetamine and caffeine, to stay awake. Just to reach their destination on time, they would forgo rest and sleep, instead driving more than 10 hours in one stretch. Zhang Keyuan had encountered truckers like that over the years. “You take it once and you don’t sleep for two days,” he said. “Some drivers cover really long distances, so they’ll buy some.”

In Shenzhen, he once saw a trucker openly smoking in front of him. He had drilled two holes into a bottle cap and stuck two straws inside, creating a makeshift hookah of sorts. Then he rolled a strip of foil into a U, added a pinch of meth, and lined it against the ends of one of the straws. Flicking his lighter open, he started heating the foil from underneath. As it started smoking, he inhaled deeply from the other straw. Then, with tendrils of white vapors escaping from his nostrils, he gently breathed out.

This sight was nothing new to Zhang Keyuan, given his years trucking. “They’ll occasionally spend a few hundred yuan to smoke it once, mostly when they’re rushed for time, but they don't usually do drugs,” he said. “It’s so expensive. Who can afford it?” He felt only pity for them. “I don't want to become like them,” he added. “If I get tired, I’ll stop and rest. I don't overthink it.”

Zhang Yaofeng had never witnessed truckers doing drugs, but he cautiously allowed that “it’s possible.” At 2 a.m., he finally drove onto the G55 expressway. Before that, we had been driving on the national and provincial highways in Guangdong and Hunan. He said that these roads were slightly more dangerous, but they would save him a couple hundred yuan in fees. We were nearing Yongzhou at this point. Zhang Yaofeng yawned and reached for a betel nut. “We’ll sleep at the Lengshuitan Service Area tonight,” he said.

Thieves on the Roof

Courtesy Southern People Weekly.

Zhang Yaofeng pulled into the service area at 3 a.m. He circled around his vehicle, checking it carefully. A middle-aged man approached him and asked if he needed help watching his vehicle. Gesturing at me, Zhang answered, “No need. The two of us will take turns tonight.” Accepting their offer would cost him money, he told me. He locked the truck door and windows before laying down on the bunk in the sleeper car. He was always especially careful whenever he had to leave the truck or during a break. Some truck drivers teamed up for their assignments; some drivers had their spouses, but as a solo driver, Zhang Yaofeng was an easy target for oil thieves.

Having trucked for more than a decade, he had encountered oil thieves before. There had been mornings when he started the truck, only to realize that his oil tank had been thoroughly emptied. While he had heard about such thieves, he had never seen them in person and grew curious about their MO.

Then, he managed to witness the entire process when he had parked to rest at a service area one night. Around 2 a.m., a group of people driving remodeled cars turned into the truck drivers’ rest area and came for the truck parked next to Zhang. As the driver slept in the sleeper cab, they pried open his oil cap and pumped his tank clean of nearly 3,000 yuan of diesel in a matter of minutes before speeding away. They had even stripped away his tires. Zhang laid in his bunk in the sleeper cab, too afraid to make a sound. A trucker had tried to stop the thieves once when he caught them stealing his oil, but he only ended up being robbed.

That night, Zhang Yaofeng was listening to the radio when he found out about the recent truck thefts along the Guantao section of National Highway 106 and the Handa Expressway in Hebei Province. Nine suspects in an open-top truck had used hooks to latch onto a trailer and stolen everything.

Thieves steal more than oil, though. Sometimes they even take cargo. Xie Rongfei, who drove for a Jiangxi freight company, shared his experience with me a few days later. Set to transport cosmetic products from Guangdong to Yunnan, he had tightly secured his trailer with a piece of tarp before departing.

Upon arrival, though, he found a long cut running along the top of the tarp. A dozen boxes of goods had disappeared without a trace. It was only later that a colleague told him how the thieves pulled it off. They drove up behind him, climbed to the top of his truck, knived the tarp and tossed the cargo from the truck into their own vehicle. As soon as they finished, they fled the scene.

“Our trucks are so big that it’s impossible for drivers to see the back,” Xie Rongfei said. He lost nearly 10,000 yuan on that assignment.

Less fortunate truckers might even be confronted by robbers directly. Around that time, we ran into a driver from Jiangsu who covered the Fujian-Xinjiang route. One night last year, he personally witnessed a couple being robbed. They had stopped to rest at a service area and were sleeping in the sleeper car, using a package as their pillow. Suddenly, an unlicensed off-road vehicle screeched to a stop right by their window. The drivers shattered the glass into pieces with a hammer, snatched the package and fled before the couple even had a chance to react. The entire incident had lasted only a few minutes.

Reporting such situations to the police was pointless, but “if you didn’t, then they have no idea that these things even happened,” the driver from Jiangsu said. Still, many drivers take the fall for the theft. They warn themselves to be even more vigilant and to flock as much as possible to more populated rest areas.

“Theft can happen; brazen robberies are rare,” Zhang Yaofeng said, maintaining a rosy outlook on public safety. Soon after he finished telling me about the oil thieves, I heard him snoring. The rest of the night passed without incident. On April 15, we rose at 8:30 to shower and brush our teeth. Then, without having breakfast, we set off toward Chongqing at 9 a.m. sharp.

Roadside Shops

We drove west along the G65 expressway, a dull stretch compared to the chaos of the national highway. The radio was airing a best-of collection of the traditional Chinese comedy routine known as crosstalk. We reached the Huaihua Service Area at noon.

Zhang Yaofeng parked and had me follow him through rows of trucks until we reached the farthest wall of the service area. “Climb up,” he said as he scaled the wall with ease. From there, a small path led to two restaurants, hidden at the end of the path. Only seasoned drivers would know about these places, which are cheaper, more popular and more filling than the restaurants in the service area.

The restaurant owner told me that their customers were all long-haulers. They had originally opened a restaurant off the national highway, but traffic decreased after the G65 expressway opened in late 2012, so they moved. “What if the service area blocks off the wall?” I asked. She laughed and said, “We’ll figure it out.”

We stuck primarily to the national and provincial highways between Shenzhen and Huaihua. As we were passing over Lanshan County, Zhang Yaofeng occasionally pointed to the abandoned homes dotting both sides of the Yonglian highway. The restaurants and inns there used to be run by villagers, he said. He had even stayed overnight before. Most of them were small, two-story structures; a handful were more refined hotels. Every building had reserved spacious lots for truck parking. Some accommodations were budget-priced and guests could play cards or mah-jongg while hotel staff watched their trucks for free or poured antifreeze into their truck. There were also call girls available, most over 30. “The younger ones went to work for hotels,” Zhang said. He reminisced over the bygone bustle of this “Road of Death” where trucks once roamed—and risk of accidents ran high.

After the G55 expressway opened at the end of 2014, fewer and fewer drivers passed through Yonglian. Businesses on both sides of the road had almost all shuttered and freight trucks no longer stopped here to rest. “The villagers who opened shops here could stand to earn tens of thousands of yuan in a year, even more than a million,” Zhang said, “but most of them had to close.”

An insider in the logistics industry told me that the overall economic environment has slowed over the past two years, with the logistics industry likewise lagging. The number of assignments and freight rates has fallen, leaving drivers with less spending money and thus affecting highway businesses. She said that for villages situated along the national highways in Henan and other places, it used to be the case that the men would leave for work, while women would look after their own homes, as well as providing food and accommodation for passing long-haulers. Some might even sleep with the drivers. “Some villages made their money that way, but people wouldn't gossip about it,” she added. However, these practices have slowly ebbed after 2012.

We left Huaihua and continued on the expressway until we reached Greater Chongqing around dusk. Aiming to arrive in time to unload his cargo the next morning, Zhang Yaofeng had driven the whole time in a hurry, stopping to rest for only five hours. He even drove through heavy rain the next day. At 6 in the morning, we exited the highway and entered Chongqing. Zhang Yaofeng unloaded his cargo before rushing off for another assignment that would send him back to Shenzhen that same day. His trip from Shenzhen to Chongqing had netted him 9,000 yuan. He would have to drive about 30 more trips to pay off his 20,000 yuan mortgage for his truck.

Just like that, we swiftly parted ways. He had done what his friend at the logistics company had asked of him. As for me, the story I sought was only half-finished. Before leaving, Zhang Yaofeng gave me an address for the call girls who serviced drivers.

The Women in the Sleeper Cab

Courtesy Southern People Weekly.

I followed his tip to the Huarong freight exchange, the largest market for freight transport located in the northern Chongqing. After delivering their cargo, thousands of drivers from all over China would flock here to park, rest or find work. The market’s three factory-style buildings housed hundreds of logistics companies that provided a range of sourcing information. For 200 to 300 yuan, truck owners could find load assignments here.

Motels and restaurants clustered in the surrounding area. Accommodations were simple and crude, ranging from 4-square meter single rooms to five-person rooms with just over 10 square meters of floor space. Some rooms were separated by a wooden board, providing only a bed, blankets, slippers, wastebasket, fan and TV. For that, guests paid 30 to 40 yuan a night. A number of locals opened family inns in the older neighborhoods around the market, offering slightly cleaner options.

As night fell and the market lights came on, the drivers swarmed the small restaurants nearby. Jiangxi trucker Xie Rongfei said that apart from drinking and talking, the greatest pastime for truckers over the decades has been gambling. Before we had finished our drinks, the sound of shuffling mah-jongg tiles occasionally surfaced from above. The bright colors of the flashing motel signs illuminated the long hallways upstairs. We went back to our motel after dinner and found the card room packed with people playing mah-jongg, poker or a Chinese card game. Unable to snag a seat, some went back to their rooms to play cards. Truckers threw aside their usual frugality and grew extravagant with their money here, winning or losing anything from 10 yuan to several hundred.

The restaurant downstairs was as raucous as before. Outside, truckers jostled for seats by the roadside food stalls. The non-gamblers among them retreated to their rooms after dinner to shower and wash their clothes. Being on the road left them with no way to shower, so many of them had accrued several days’ worth of sweat and grime. Afterward, a few of them stayed in their rooms to watch TV or talk. Others wandered the shop downstairs or hung out outside. A motel staffer came over and asked if they wanted to hire out a call girl. “Cheap—only 120 yuan per session,” she hawked with a smile. “One phone call is all it takes.”

This motel only had one call girl, who lived in her own place nearby. Once a call came through, she would grab her purse and arrive at the client’s room within a few minutes. At the end of the session, she would continue down the hallway, knocking on doors and looking for her next client. In a small place overrun with men, the sound of her heels clacking on the ground made her hard to overlook.

I caught a glimpse of her from our card room. An attractive woman around 30, she was dressed in a black wraparound and stockings, her perfume hanging heavy around her. She was surnamed Zhou and she only serviced drivers. She had grown up in a village in the outskirts of Chongqing and had lived a comfortable childhood, at least compared to families deeper in the mountains. Her previous job was stapling buttons at a local clothing factory situated close to a highway, which allowed her to occasionally slip away with a co-worker for lunch at one of the roadside restaurants. The affordability of those restaurants attracted the business of many truckers, which is how she met a long-hauler from the northeast. Eight months later, Ms. Zhou became his wife.

Once married, she left her job. She would sometimes travel with her husband, cooking for him and washing his clothes, experiencing a kind of adventurous lifestyle that both piqued her curiosity and excited her at the same time. That all ended one day, though, when she stumbled upon the truth of her husband’s infidelity in a phone message. He had been soliciting call girls and had had an affair.

Infuriated, she divorced him and returned to Chongqing, where she worked as a supermarket cashier. When she saw that truckers were making more and more money, she decided in 2010 to start selling her body, becoming the very call girl that her ex-husband used to solicit. She was 28 then. Sometimes she would have 10 calls a day. On other days, there would be nothing. The motel took part of her earnings, but otherwise she stood to earn 100 yuan per gig. The downturn of the logistics market in the past two years has taken a toll on her earnings, although she still earns enough to cover basic necessities.

Some drivers gave her repeated business and eventually became friends. In 2012, a Jiangxi long-hauler named Zou Rong would hire her out whenever he came to Chongqing. “He said he liked me, but he had a wife and kids at home, which isn’t my type,” Ms. Zhou said. One day, he offered her 2,000 yuan if she rode with him to Fujian. She thought he was joking and countered with 3,000 yuan. The next day, they set off together for Quanzhou, Fujian Province. Her job along the way was chatting with him, helping him pass the time and sleeping with him. When they reached Quanzhou, he took her shopping and bought her clothes and handbags.

Many of the drivers I met said that having a call girl as a travel companion was common, albeit not universal. “Most truckers are far from home most of the year,” Ms. Zhou said. “It can get boring and lonely.” The other call girls she knew had also traveled with drivers before, though they sometimes encountered questionable characters. One of them had once traveled with a Xinjiang-bound long-hauler who, dissatisfied with her service, gave her 3,000 yuan and left her in the Gobi Desert in Gansu Province. She had to walk over 10 kilometers before she reached a village. “That was cruel,” Ms. Zhou said, her face clouded with anger.

Last year at the motel, Ms. Zhou met a trucker from the northeast who was nine years her junior. He had his own flatbed truck and often came through Chongqing on his routes, along with a team driver from his village. He often gifted Ms. Zhou with clothes and after a number of sessions, she came to like him. This was the first time she had developed feelings for a client since joining the industry. Several months later, the young trucker was left on his own after his team driver had to return home, so he decided to bring Ms. Zhou along instead. They traveled from Chongqing to Shandong, then from Shandong to Xinjiang.

Over three consecutive months, they spent most of their time in the sleeper cab of the truck. Along the way, she cooked for him and cleaned for him. Ms. Zhou thought back to traveling with her ex-husband all those years ago and realized that she had been single for some time, which only spurred her to take even better care of the young driver. “I was his girlfriend,” she stated simply. Looking back, those were her happiest times in recent years.

She even entertained thoughts of settling down with him, but late last year, he suddenly vanished from her life and they lost contact. “He’s probably married,” she said, lowering her head. Now 34, she yearned to have a family of her own.

The next day, I caught a high-speed train to Chengdu. I wanted to visit a Tibetan friend in Chamdo, Tibet and was hoping to catch a ride with a trucker heading that way, but nobody would take me. “We don't even know you,” one driver told me. “Who knows if you’re a good person or not?”

“Ba-dum-tss. Feel it!”

I had no choice but to return to Chongqing, where I started looking for a ride back to Guangdong via Guizhou and Guangxi. While I was there, I stayed at “Drivers’ Home,” a hotel managed by 35-year-old You Wenshen, who had previously worked at a logistics company in Shenzhen and knew a number of long-haulers. In 2011, he had moved back to his hometown of Chongqing and opened a family motel in Zengjia Village, catering specifically to truckers stopping in Chongqing for repairs. Food and housing cost 50 yuan a person a day. Because of his hospitality, truckers all referred to his place as “Drivers’ Home.”

On the morning of April 20, I caught a ride to the Tuanjie railway station in Chongqing with Liu Jinli and his wife. They had also stayed at “Driver’s Home” and were on their way to load cargo. There were three cars that day set to transport cargo to Liuzhou, Guangxi before returning to Shenzhen. Then I ran into Zhang Keyuan. Perhaps it was because we were close in age that we got along well, and he agreed to take me with him.

With his bespectacled appearance, he was easy to spot among the truckers. Originally from Linshui County in Sichuan, the now 35-year-old Zhang Keyuan had had a short-lived career working on the assembly lines at a Guangzhou factory at 17. He struggled to adjust and left. Later, he went back to Sichuan, where he drove agricultural vehicles, vans and trucks transporting coal. In 2003, he bought a secondhand truck in Shenzhen and started long-hauling. He used to repair cars when he was younger, but he said that electric welding had damaged his eyes. Now, his greatest joy while on the road is calling his wife and messaging on WeChat.

The boredom set in about 10 hours after we had left Chongqing, so I started playing Chinese rock band Miserable Faith’s Highway Song on my phone. Zhang Keyuan said that the only way to feel the music was to blast it, so he had me connect to his Bluetooth. Not much later, he started shaking his head. “It’s too low-key, too soft,” he said. “It’s lulling me to sleep.”

“What kind of music do you like?” I asked.

“DJs—the kind at bars,” he animatedly explained, trying to mouth-drum. “There’s so much energy there. Ba-dum-tss!”

I wordlessly turned off my phone.

Around 8 p.m. that night, Zhang Keyuan pulled into the Duyun Service Area, ate a 25 yuan dinner at the canteen and went back to his truck to sleep. The next morning at 4 a.m., we set off on National Highway 210 and soon arrived at Guangxi. The terrain on both sides of the road shifted, gradually and then suddenly, as the distinctly craggy mountains of Guizhou gave way to smoother hills and the leveled earth became more expansive.

Around 6:30 a.m. on April 21, we reached Lazhe Village in Guangxi, which sat on intersection of National Highway 210 and the G75 Expressway. The road ahead snaked and sloped. On a rainy day two months ago, Zhang Keyuan’s friend had crashed his truck. As he recounted the incident, he kept stepping on the brakes.

A few minutes later, as the flow of cars slowed to a stop, we hit a traffic jam that snarled over several kilometers long. “Car wreck,” Zhang Keyuan said knowingly. We sat for nearly half an hour, even as the logjam grew. Zhang started boiling water and readied two servings of instant noodles, each with half a packet of pickled veggies. This was our breakfast. An hour-and-a-half later, emergency vehicles finally rushed past us.

I got out and walked 500 meters up the road through the row of cars until I saw the cause of the jam ahead. Two trucks had collided headfirst. The sleeper cab in one of the trucks had been badly twisted. The bumper and car doors had fallen off and were being dragged to the side of the road by rescue workers. The sleeper cab and trailer of the other truck had completely bent into an L. It was nearly unrecognizable. Its fuel tank had fallen, the ground strewn with metal fragments of all sizes. One of the workers snapped photos and explained that fatigue had caused one of the truckers to swerve outside his lane into the oncoming truck.

By 8:40 a.m., a narrow lane had finally been cleared through the wreckage and we started moving once again. I had taken two photos of the accident and shared them with Zhang Keyuan. “Minor,” he said, nonplussed. He showed me a video from his route to Ruili, Yunnan this past February. A fully loaded truck, going downhill on a hairpin turn, had caught fire. Plumes of heavy smoke rose from the carnage.

I had seen that kind of devastation before in Chongqing. Two days ago, I was staying with Zhang Junli, a truck owner from Jilin who showed me photos from his car crash in May 2009. At the time, he and his two trucks were hauling about 20 brand-new Volkswagen cars from Changchun to a dealership store in Chongqing. He had only joined the trucking industry six months prior but had spent close to 900,000 yuan on two Jiefang trucks, one new, one secondhand. He had also hired four team drivers. After they had passed through Qin Mountains, the road sloped downhill for nearly 10 kilometers, but that persistent braking, coupled with the trucks’ overweight load, caused the tires and the brakes to overheat. The vehicle started smoking and then burst into flames.

Zhang Junli saw the fire from his rearview mirror. Horror-stricken, he shouted at his driver to stop and jumped off. He ran pell-mell toward the scene and dialed for help. The flames quickly spread from the tires to the truck, followed by the fuel tank, the battery and the Volkswagen vehicles. One after another, they exploded into flames. Everybody at the scene could only stand and watch it burn. Even the firefighters were afraid of approaching.

“The aluminum engines of the passenger cars had all caught on fire,” Zhang said. “By the end, there was only chunks of aluminum left underneath the truck.” All told, the fire had destroyed his two trucks, a section of the expressway and 12 of the passenger vehicles, including an Audi A6, a Magotan and a Sagitar. The damages altogether totaled more than 4 million yuan. Zhang Junli had to pay the dealership 300,000 yuan out-of-pocket and hitch a ride home. Insurance covered the remaining costs.

The accident changed his life. He had to wait for the fire department to issue him proof of the accident, which cost him another two weeks in Hanzhong and 1,000 yuan more. Then, when he was back in Chongqing to file his claim, his truck bumped into the curb. City management officers surrounded him and demanded a fine, even shoving him. Bursting into anger, Zhang Junli pulled out a long knife from his sleeper cab and waved it at them to intimidate them. For that, he was sentenced to reform camp for several months. He is now one of China’s most well-known petitioners.

The roads in China are home to an abundance of car accidents every day. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, there were 34,300 motor vehicle fatalities across all the national highways in 2014. However, the World Health Organization has reported more than 200,000 deaths in China annually in recent years, a figure that far surpasses the government’s official count.

Road safety signs line both sides of the road. Some send a sterner message, warning drivers to slow down because of dangerous conditions ahead or reminding them of the risks of speeding. Some offered gentler reminders, even humor: “We Plead with Your Highness to Drive Carefully, Lest Her Majesty Awaits in an Empty Home” or “Slow down. Your Father Isn’t a Big Shot Who Can Bail You Out.” With the Nandan accident not far behind us, we continued to come across a number of bends and steep inclines along the National Highway 210. At one hairpin bend, we saw a severely damaged van. The sign above it read: “Fatalities from Speeding the Curve Ahead: 14.” The number—underlined, ready to change at any given moment—stood as a warning to drivers.

The Folks in Uniform

The truckers were used to accidents and fatalities, so they didn't flinch like I did. I thought of the ones who downed liquor while driving. Maybe, just maybe, passing away so suddenly in a semi-conscious, half-drunk state was one of the outcomes they were hoping for. But riding with Zhang Keyuan, I realized that truckers had even greater worries than that.

Soon after leaving Nandan County, we turned onto National Highway 323 and drove into the city of Hechi. It was nearly 11:30 a.m. by then. Zhang Keyuan had originally planned on reaching our destination of Liuzhou by noon, but foiled by the sudden car crash, he decided to get on the expressway via Hechi.

As we approached the city, more and more trucks started pulling over to the side of the national highway and killing their engines. “Another crash?” I asked.

“Aside from trucks, the other cars are still going,” he replied. “There’s probably a police checkpoint ahead.”

We continued a few hundred meters before we saw a police car parked under a tree. Four officers sat inside, staring at passing traffic, resting with their heads thrown back or looking at their phones. Nearly a dozen trucks had stopped just a short distance away on the other side of the road, with most of the drivers resting.

“Why are they stopping?” I asked, curious.

“They’re waiting until the traffic cops finish their shift and leave,” Zhang Keyuan explained. “All my cargo is standard. The dimensions, the weight—they all conform to European standards. The police won’t flag me, but the other trucks stopped because theirs don’t. They’ll be fined if they pass, or at least the police will find a reason to fine them.”

With the rapid expansion of China’s expressways over the past decade, truckers have increasingly flocked to expressways because of their convenience and safety. But the expressway tolls in certain areas can be exorbitant, even as freight costs have decreased. Driven by financial considerations, some drivers have started going back to national or provincial highways, but those routes happen to draw more inspections than anywhere else.

A trucker from Jiangsu said that they usually know how much they’ll be fined from the way law enforcement officers wave their hands. Overweight or oversized cargo is inevitably subject to fines, although unclean lights, license plates, or windshields can also sometimes draw a fine. “Traffic police levy lighter fines. The highway administration charges hefty fines,” he said of his own experience. “Sometimes they don't even write up the fine, so it’s more like paying them a toll. That’s one of the unspoken rules of this industry.” Over the years, he has learned to compromise.

No fan of traffic police, Zhang Junli said that he had had to pay fines totaling 20,000 yuan within a year of buying his truck. His mistrust only deepened after an incident in early 2010 when his vehicle was impounded. At the time, he was on assignment transporting passenger vehicles for a dealership. From Changchun, he was passing through Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, when the local police stopped him for an inspection and arbitrarily fined him. Confused, Zhang Junli asked them to give a reason, so they determined that his truck had been modified—a 10,000 yuan fine. He refused to pay, so they impounded his truck. He spent a few days fruitlessly trying to argue his way out, even as the dealership kept haranguing him to deliver the cars. Enraged, he unloaded all the passenger vehicles from his truck and lined them by the entrance of the impound lot.

He finally had the attention of the local police. After digging up his records, they saw that he had previously survived a fire and had even had a dispute with Chongqing urban management officials, which led to some 100 days in reform camp. Afraid that he might cause a disturbance, they offered to intervene with the traffic police on his behalf. “Ultimately they returned my cars to me and cancelled the fine, but I was delayed by a week and had to pay the dealership,” Zhang Junli said.

After multiple instances of being fined, Zhang Junli gradually grew rebellious. Once a traffic cop, claiming that his truck was oversized, tried to stop him and fine him just after he had gotten on the expressway. Instead, Zhang Junli sped up. The police car gave chase, hot on his trail like a scene from a cop movie. “Another time, an officer wanted to fine me for some misdeed, so I gave him 500 yuan, but he straight-up said that it wasn’t enough for everyone to split,” Zhang Junli said. After that, he no longer wanted anything to do with the police. By the end of 2010, he had sold off his own truck and quit the industry.

“There’s probably something wrong with a truck if it gets stopped,” Zhang Keyuan mused. He pays a couple thousand yuan each year in fines. We passed through Hechi City and got on the expressway. Nearly two hours later, we reached the loading dock in Liuzhou, but the factory building was filled to capacity with trucks that needed unloading. “The trucks that arrived yesterday haven’t been unloaded yet,” Zhang said. “I’ll probably have to wait until tomorrow.”

Zhang Keyuan and I parted ways, and I headed back to Guangzhou. I felt like a camphor tree by the side of the road, the scenery that swiftly disappears from the truckers’ horizons. Later, Zhang Keyuan told me that he accepted a last-minute assignment to Wuzhou, Guangxi, instead of returning to Shenzhen like he had planned. Nowadays, he all but accepts any work that pays, instead of haggling over freight rates. He wants to make enough money to send back home, but he hates that the logistics company uses fuel cards to offset freight expenses—he had just topped up for nothing.

Government policy on value-added taxes (VAT) shifted after 2012. Logistics companies no longer paid truckers in full in cash for transportation costs. Instead, they use fuel cards to offset at least half the payment, a trend that has only worsened over time. “Companies do this to evade taxes, which then fall on us,” Zhang said. “We get lower rates for cash with fuel cards, and some gas stations now won't even take them.” At times, Zhang Keyuan has a gloomy outlook on the industry. Talking about fears wrought by risk factors—the toll on their bodies, long-term smoking, and fire accidents—has made him think of quitting on several occasions.

Later, he messaged me on WeChat to say that if I ever traveled to Yunnan, he was willing to take me for free. His offer made me think of the friends I had made throughout the different stages of my life. Zhang Keyuan recently left on an assignment, hauling a shipping container from Shekou, Shenzhen to Chongqing, thus kicking off yet another road trip.

Lin Yijing, Yuan Feng and Liu Piao contributed to this story.

Translator: Katherine Tse