Greetings from Chinarrative!

In this issue we feature the writing of Kathy Huang, who examines a topic on many people’s minds in the wake of the Shanghai lockdown: How do I get out of China?

There’s even a term for it: runxue, or the study of running away. “China's forever lockdowns have caused some to look for a radical solution: to emigrate, or run away from what they see as a lost future in China,” Huang writes.

This piece originally ran as a blog item on the Council on Foreign Relations “Asia Unbound” column, where CFR fellows and other experts assess the latest issues emerging in Asia today. Views expressed are not those of CFR, however, which takes no institutional positions.

Thank you to Huang and CFR for their kind permission to republish.

Huang, who is a research associate at the council, grew up in China’s Zhejiang province. She’s a graduate of Wesleyan University, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in government and East Asian studies. Her current research is focused on China’s domestic and foreign politics, and on the country’s internet space.

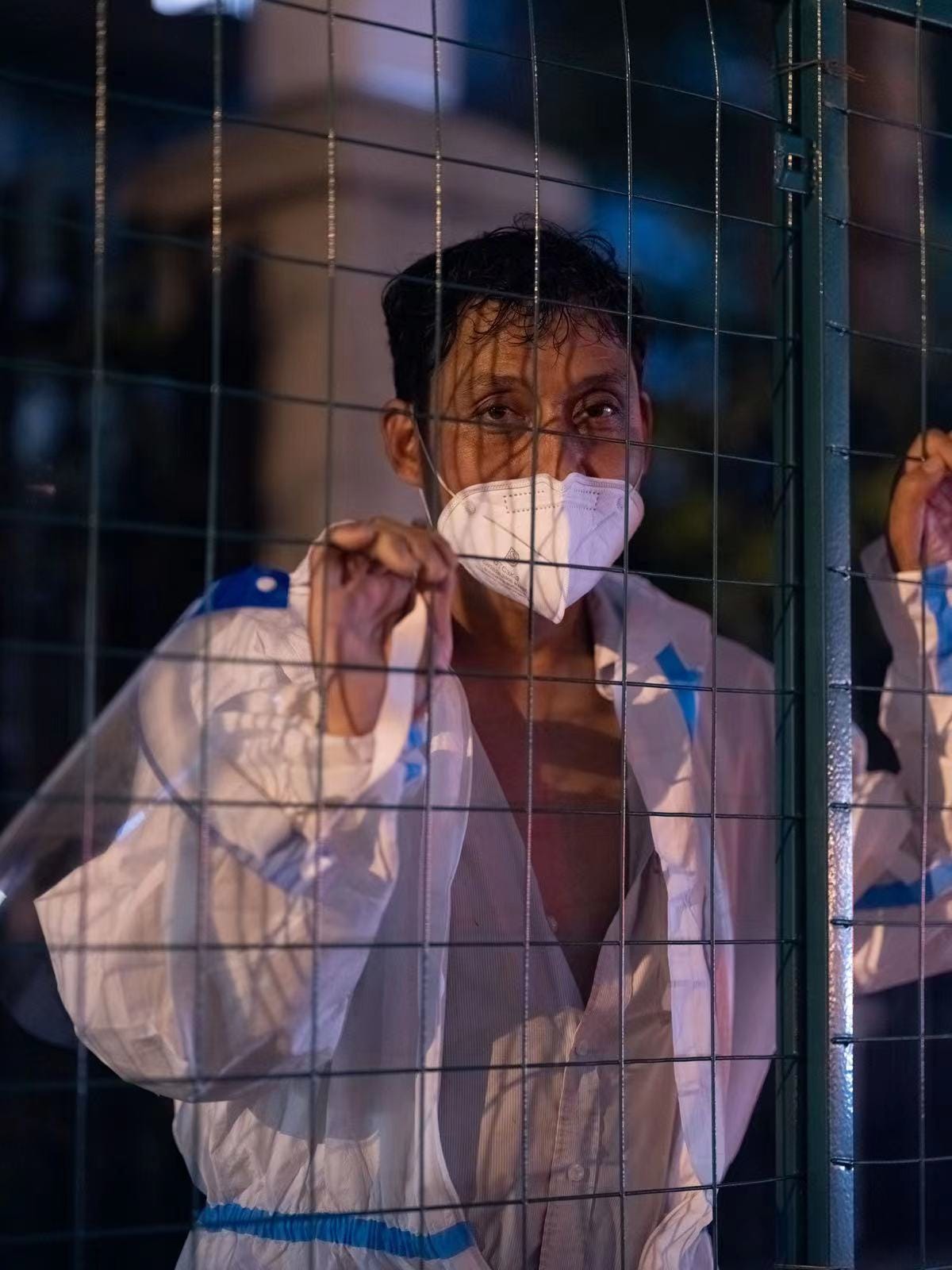

Photos by the talented, Shanghai-based photographer Zhou Pinglang, are an added bonus only for our readers.

Thanks for your continued support of Chinarrative. If you’d like to become a founding member or a paid subscriber, please click below. You can also follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Runology: How to Run Away From China

By Kathy Huang

In years past, some young people tried to escape the pressures of life in China—high housing prices, fierce employment competition, lack of work-life balance—by dropping out, or what was known in Chinese as “lying flat,” or tangping.

Now, China's forever lockdowns have caused some to look for a more radical solution: “runology,” or runxue in Chinese.

The term plays on the romanization of the Chinese character 润, or run. It means “profitable” in Chinese, but its romanization run makes it a code word for running away, or emigrating overseas. It's added to the character for “study,” xue (学), making the meme something like "the study of running away."

The term went viral at the beginning of the two months-long Shanghai lockdown, which started in early April and is only ending on June 1. (Editors note: As we publish, parts of the city are back under lockdown once again.)

Residents were confined to their homes with limited access to food and healthcare. The goal: to follow the party’s rigid “dynamic zero-Covid” policy, which deploys mass testing and strict quarantine measures to contain any potential outbreaks.

Adding to the sense of helplessness is that this was not China’s first Covid lockdown. Wuhan was the first city to go through a two-month lockdown at the beginning of 2020, followed by Xi’an, Harbin, and Shenzhen at the end of last year and earlier this year.

The impact of the Shanghai lockdown, however, has grabbed people’s attention in China and abroad. China’s largest city and financial hub, Shanghai has a diverse population of foreigners and many young Chinese with international backgrounds.

The global and relatively liberal image of the city collided with the horror stories recorded online during the lockdown. Chronically ill patients ran out of medication, pets were beaten to death on the street for potentially exposing people to Covid, while authorities have broken into houses to forcefully sanitize them.

For many Chinese people, this lockdown became emblematic of disillusionment with government policies. That has caused some to look to emigration to essentially “run away” from what they see as a lost future in China.

On April 3, the same day the government reiterated its “dynamic zero-Covid” policy, the number of searches for “immigration” increased by 440% on WeChat. Canada being the most popular destination, Tencent reported that the phrase “conditions for moving to Canada” increased 2846% in the week of March 28 to April 3. The number of inquiries to immigration consultancies has also skyrocketed in the past month.

As the term has grown in popularity, “runology” became no longer just a synonym for “emigration,” but a study of why, where, and how to run away.

Users on online discussion platforms such as Zhihu share their interpretation of the phenomenon and provide practical guidance on how to emigrate. The viewpoints are diverse: not everyone is blindly calling for emigration as the sole solution to problems, but many regard it as a viable alternative to their living conditions in China today.

If this sort of widespread dissatisfaction lasts, trends such as “runology” could pose challenges to the Communist Party’s goal of growing China’s talent pool. In an important speech last September, Chinese President Xi Jinping highlighted the cruciality of cultivating, importing, and utilizing talent in China’s new era: “Never in history has China been closer to the goal of national rejuvenation and never in history has it been in greater need of talents people,” he said.

Xi also emphasized the need for China to “self-cultivate talent” while also avoiding “self-isolation.” Half a year later, both goals seem far away.

The extensive quarantine rules for traveling hinder any talent inflow, while the lockdowns are prompting talent outflow.

Big data predicted the number of students abroad who returned to China for employment would exceed one million for the first time in 2021, according to the National Development and Reform Commission. But how to retain young talent remains a serious problem for the party.

For many, the Shanghai lockdown is only the final trigger. Besides running away, some young Chinese see their options as limited to another popular term from recent years, neijuan, or “involution”—to participate in the highly competitive environment with few opportunities to succeed, and “lying flat.”

None of these options reflect the optimal environment for cultivating talent. Although it takes much money and effort to emigrate—making it unclear how many really will go abroad—the spike in interest at least shows that many young people are dissatisfied with their current environment.

Perhaps what is most significant about the Shanghai lockdown for many is the epiphany that government policy trumps all in China: no matter one’s economic status, one can be subject to arbitrary government policy anytime that clashes with other priorities young people have.

Freedom, not necessarily politically but at least physically, is becoming an important index of how people evaluate their lives.