Finally, I Don't Have to Work Tomorrow

No. 49

Greetings from Chinarrative!

This is the first of a two-part, long-form feature published recently by Media Fox (极昼工作室), an online media company affiliated with Sohu News. The writers—Cai Jiaxin, Yin Shenglin and Li Xiaofang—delve into the extreme work culture of Pinduoduo, an e-commerce firm that has grown rapidly into one of China’s tech titans.

Their work is timely. The deaths of two Pinduoduo employees since late December—one by suicide, one following a medical emergency sustained after working past midnight—has renewed scrutiny on labor practices at China’s big technology companies, many of which notoriously demanding that staff work so-called “996” schedules: from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week.

Through interviews with several former employees, the article shows the immense pressure on employees who endure long hours of overtime and could be fired at a moment’s notice.

We must stress that no straight line has been drawn between the two recent deaths and Pinduoduo’s work culture as described in this article. Chinarrative, as a translation platform, hasn’t independently verified the claims made by the Media Fox reporters. Comments by Pinduoduo regarding recent events can be found here (in Chinese).

Look out for the second installment of this story in your inbox soon.

To become a paid subscriber just click through the “Subscribe now” button below—it’s $5 per month or $50 per year. Founding member slots are also still available! Past issues are archived here. Contact us at editors@chinarrative.com for thoughts, story ideas, or to chat about original submissions.

Finally, I Don’t Have to Work Tomorrow

By Cai Jiaxin, Yin Shenglin and Li Xiaofang

Chen Rui was a typical Pinduoduo guy. He often got off work after 1:00 a.m., worked 12-hour shifts and could work for 42 days in a row. He never ate lunch before 12 p.m. and was back at his desk before the end of the evening break at 7 p.m.

When he didn’t have toilet privileges, he held it in. He didn’t openly voice his opinions and rarely complained. He was very clear that his deal with the company equated a high salary with high pressure.

Honesty. Diligence. Focus. Not seeking advantages. Taking responsibility. Chen can reel off the values that, according to Pinduoduo founder Colin Huang, constitute the “duty” of all employees. To Chen, the core of this ethos is making sure you do your job as well as possible.

Despite that, this archetypal Pinduoduo employee recently “was resigned,” a Chinese euphemism for being told to quit.

It happened in December. Chen, the back-end engineer of the grocery shopping project Duoduo Maicai, had worked for 20 consecutive days. The following day was Saturday, and he wanted to take it off. This isn’t the attitude a Pinduoduo guy should take, but Chen knew the “Double 12” shopping festival was coming up, and if he didn’t rest tomorrow, he’d not get another chance for three weeks, taking him to nearly 40 successive days of work. The last time he did that, he had pain in his knees and low stamina. At only 27 years old, it was hard to carry things up the stairs.

At 10 p.m. that evening, after hesitating for much of the day, Chen circled round to the desk of his team leader, who sat diagonally opposite him.

“I was thinking of taking tomorrow off,” he said, quietly, so only his team leader could hear him.

“Have you finished all your work?” came the response.

“Yes.”

His team leader stared silently at his computer for around five seconds, “fine.”

Chen resented his group leader’s reluctant tone and his own ingratiating approach. He thought to himself:

Why do I feel like I have to request leave, just to have a normal day off?

That night, he couldn’t sleep. After turning things over in his head, he decided to take a new tack: to “not contribute anymore” and “seize any chance to be lazy and take things a little easier.”

On Saturday afternoon, he went to the supermarket. Cooking was one of his few pastimes, but he hadn’t done so since his last day off nearly three weeks ago when he made kung pao chicken and fried shrimp. Suddenly, a message from his team leader appeared in his work group chat.

Colleagues who plan to take Saturdays off must ask for leave from me and the manager above. I recently found out that our team has been the first to leave at night. Other people asked me several times why our team has left so early… I can’t rule out that some colleagues don’t have enough work to do, so please send me your feedback. Overall, we still have lots to get through.

Chen was furious. He took a screenshot of the chat history and posted it anonymously to the social-networking platform Maimai, with the note:

Duoduo Maicai: Leave later than normal, get gaslighted and ask for leave if you want a day off!

Pinduoduo was Chen’s first job after graduating from college, and it hadn’t been easy to get. As a mechanical science major, he was effectively switching to the internet sector from the get-go. When the recruiter said he would work six days a week, he accepted it. After all, Pinduoduo generally paid more than the industry average; some of his peers were earning 5,000 yuan (around $770) less per month for similar positions.

Money wasn’t his only motivation; Chen also wanted to see “how this product used by people across the country is made.”

On Sunday, Chen went to work as usual, working overtime until 3 a.m. The following day, he returned to the office by 1 p.m.

At around 10 p.m., before his shift was over, Chen was suddenly called to the ninth floor. Three company administrators sat before him. One of them raised his mobile phone and asked: “did you send this?”

Chen nodded. “Why did you send it?” the other party asked. Before Chen could explain, the administrators leveled a series of accusations at him: “first-degree violations,” “leaking company secrets,” even causing “malicious slander to the company.”

That had been the second day Chen had anonymously vented his frustration on Maimai. The post had only received around 10 replies before it was swallowed up by others. “I didn’t expect to be found out so soon,” he said.

He had sent the post from home, and thought that if Maimai hadn’t leaked his personal information, then the most likely scenario was that there was a problem with the company’s office software that he had installed on his phone. Later, several former colleagues told him their bosses had suddenly sent them messages criticizing their supposedly low workloads while they were talking in private group chats.

He remembers that his superiors on the ninth floor gave him two choices: voluntarily quit within 10 minutes, or get a black mark on his resignation documents.

There was no other way. Five minutes later, he signed his name.

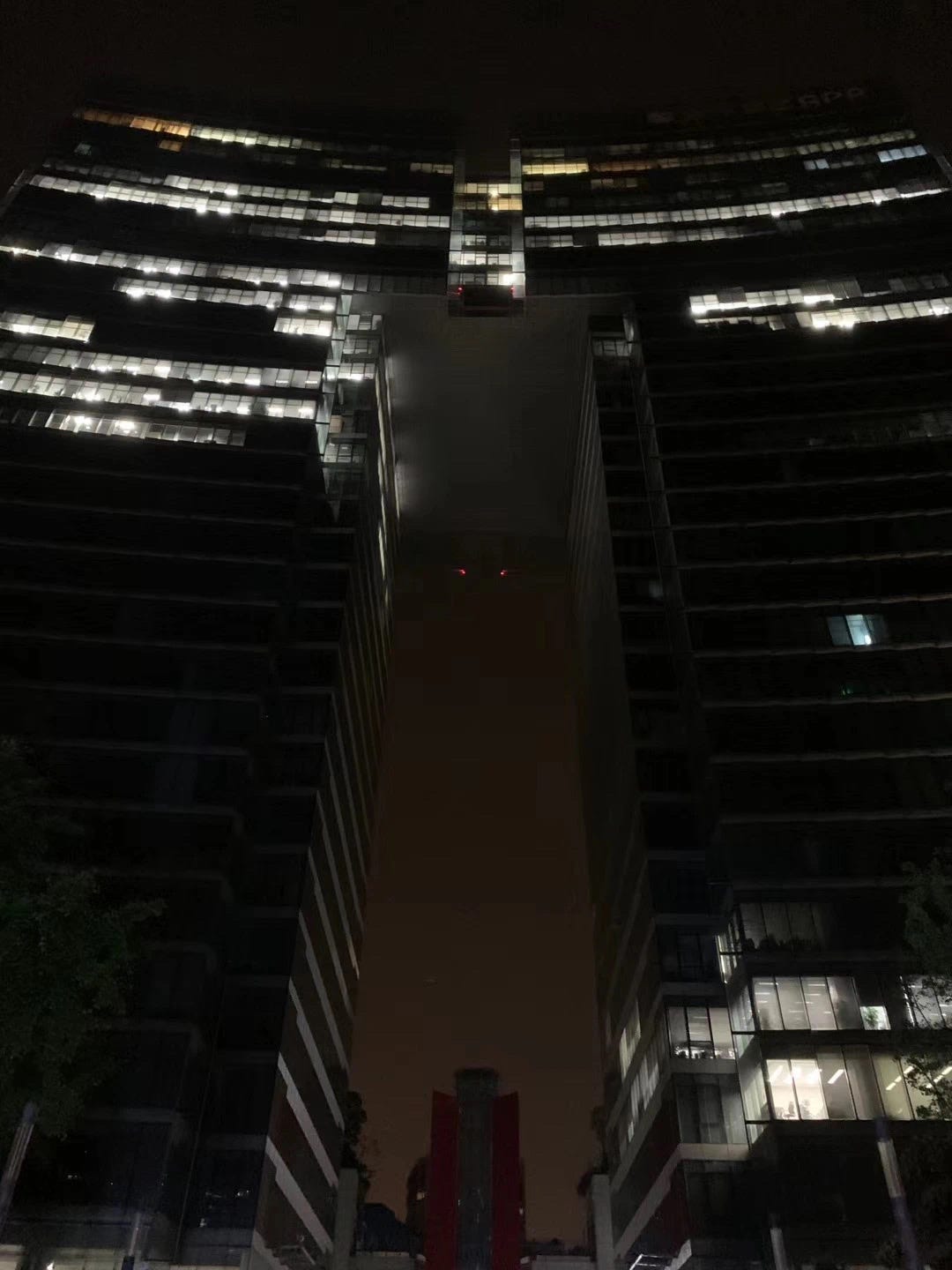

His supervisor and an administrator took him to return his work card and then accompanied him back to his workstation to pack his things. By now, it was about 10:30 p.m., the prime working hours of this internet company with some 7,000 employees and a market value of $200 billion. A former Pinduoduo employee said that by 11 p.m., the company’s Shanghai office “has so many brightly lit floors—that’s how you know they’re all there.”

As Chen silently packed his books and teacup into his rucksack, the dozen or so other colleagues in his team stared fixedly at their computer screens.

He walked alone back to the room he rented. It wasn’t yet midnight, the earliest he’d gotten home in months. He was a little upset about whether he should have sent that post. Not only had he lost his year-end bonus and signing-on fee, but he had also worked for less than a year during tough times for job hunters.

But there was a hint of glee amid the sadness. He thought:

Finally, I don’t have to work tomorrow.

‘Benfen’ at Core of Corporate Culture

Many Chinese college graduates dream of working for a big internet company. The industry has surpassed fast-moving consumer goods, real estate and the media as the site of frantic competition among young people. According to a graduate who submitted dozens of resumes in the autumn of 2019 before finally getting a job at Pinduoduo, every major internet company has certain preferences.

Most graduates hired by Tencent are highly self-sufficient and active in social clubs. Those who go to Alibaba are practical and driven, and equally as intellectual as they are emotionally aware. ByteDance recruits tend to have a lot of creativity. And those at Pinduoduo? They’re able to deal with a huge amount of hard work.

Chen meets those requirements. He graduated from a top Chinese university with the fourth-highest grades of anyone on his course, started studying algorithms a year before he left college, and taught himself how to code in the Java programming language.

When some people complained online about Pinduoduo’s system of fining staff three hours’ salary for arriving one minute late to work, Chen would take it upon himself to clarify that the rules were meant to dissuade latecomers from affecting the work schedules of other teams.

The concept of “benfen” lies at the heart of Pinduoduo’s value system. The term is sometimes translated as “duty,” although it encompasses a broader range of traits:

Being honest and trustworthy; discharging one’s duties and responsibilities regardless of others’ conduct; insulating one’s mind from external pressure; never taking advantage of others even when in a position to do so; reflecting on one’s own actions; and taking responsibility when problems arise instead of blaming others.

In the view of former employee Li Xiang, these demands have been reshaped so that they fall disproportionately on the shoulders of low-level employees. Demanding that people adhere to “benfen” is akin to making them “work assiduously like a tool, without complaining or indulging in impractical fantasies,” he said, adding that Pinduoduo made him feel the most oppressed of any company he had worked for.

At Pinduoduo, a “benfen” person can throw themselves into their work to the greatest possible extent. Most employees must follow the so-called “11-11-6” system, working at least from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m., six days a week. They must accept the high stress of their jobs. At lunchtime, they have a one-hour break. The company delivers meals to the upstairs dining room, where staff collect them and take them back to eat at their crowded workstations. The company provides food and accommodation within a 10-minute radius of the office. Every day, the cycle begins again.

True Pinduoduo types make sure they strictly abide by the company’s rules. Some are in the employee handbook, while others are obscure and unwritten. For instance, many staff feel they are not allowed to ask for leave; those who have to take some may only take one day at a time, never two. You may take 10 minutes to go to the toilet, but not 15 minutes. One hour and half for lunch are fine, but two hours is out of the question. “Doing what you’re told to do—that’s ‘benfen,’” said a former staff member of Pinduoduo’s technical department.

While there is no strict formula for defining how much “benfen” someone embodies, the apparent lack of rules actually means there are rules everywhere, Li said. “At any moment, you might cross that hidden red line.”

On his first day at Pinduoduo, Li suggested setting up a WeChat group for people who joined the company at the same time, saying he felt it was “fateful that we all came on the same day.” Later that day, his supervisor severely criticized him for his actions. Another time, Li returned exhausted from a business trip and spent his lunch hour napping at his desk, a common enough practice in Chinese offices. A company vice-president came over and banged on his desk, asking why he was asleep. He looked up blearily before stealing an extra 10 minutes. He said:

It felt like being in a 19th-century textile mill.

That time, he happened to pass by the desk of an executive who was in a meeting. On the desk was a form marked in various colors, with data showing when employees had worked overtime. “Staff who frequently leave at 8 p.m. must be carefully watched,” the form read.

Without knowing when it started, some employees began to internalize the company’s work culture. Li said that when he first joined Pinduoduo, he felt his “benfen” may be a force for good: honesty, diligence, respect for rules. He was willing to uphold values like that.

Once, when he told a colleague recruitment fair that he was from Pinduoduo, the audience laughed at him disdainfully. At the time, Pinduoduo’s stock price was stagnating. “We were synonymous with fake products, just like China’s early manufacturing industry,” he remembers. “It was tied up with notions of poor quality. Nobody thought (joining Pinduoduo) was very glorious.” Still, Li felt angry and asked the amassed students how many of them earned enough to live independently from their parents. He said: “I didn’t think they were qualified to laugh at Pinduoduo.”

He also tacitly accepted the company’s culture of calling people by pseudonyms or nicknames. Even after returning to his dormitory at night, Li would not have any deeper exchanges with his colleagues. He left the firm without ever knowing his roommate’s real name.

According to Li, when he joined Pinduoduo in 2018, the average age of company employees was 26 years old. At first, he thought this might be accidental. But later, Li speculated that this became part of company strategy—after all, young people can work more overtime, their bodies are healthier, and they can withstand more stress than longtime workers.

“The people at the top of the pyramid are very driven,” said Li, adding that smarter people were more likely to adapt to the way the system worked:

They really have no need for any systemic procedures of restraint. They are the system.

Huang, Pinduoduo’s founder, has previously said in interviews that “benfen” has become the company’s culture and a strong source of its competitiveness.

At Pinduoduo, staff often tease each other with talk of “benfen.” “Are you being ‘benfen’ this morning?” is a way of asking whether a colleague checked in at 11:00 a.m. that day. “Are you going to be ‘benfen’ at noon?” questions whether the colleague will stay at the office through lunch. If they find out that a colleague has been punished or is doing something as simple as reading a book at the office, staff might say they’re not being “benfen” enough. Li said he later realized:

When everyone ridicules this, it proves nobody buys the company’s values anymore. It has collapsed, and nobody really recognizes what it is anymore.

(To protect their privacy, the names of the people in this article have been changed.)

Translator: Matthew Walsh

Contributing Chinarrative Editor: Isabel Wang