Hello! This week we present the third installment of our ongoing series, the Chinese of Fifth Avenue. (Catch up on Part 1 and Part 2.)

In Part 2, our reporting revealed that today’s increasingly affluent Chinese tourists aren’t all that impressed with the Big Apple’s most famous street and its vicinity any more.

Still, that doesn’t mean their appetite for American and other foreign luxury goods has waned. Enter the surrogate shopper.

Historically, the Chinese overseas personal shopper, or daigou, existed because international travel was beyond the average Chinese budget and there were a dearth of quality foreign brands in China.

China has since outgrown that phase, with the rapid increase in household incomes and foreign name brands aggressively expanding their retail footprint on the mainland.

But substantial import duties and the simple matter of math and convenience translate into a viable niche for the surrogate shopper. Yet as Chinarrative contributor Alex Fang reports, even that narrow window of arbitrage is fast closing.

New to Chinarrative? Subscribe here. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Past issues are archived here. Thoughts, story ideas? We can be reached at editors@chinarrative.com.

Surrogate Shoppers’ Days Are Numbered

By Alex Fang

When it’s is her turn to check out, Sunny Li* puts five handbags on the counter, and pulls out an inch-thick bundle of assorted dollar bills from her satchel.

Li, a 24-year old originally from China, has long, bronze hair, straight bangs, and a pale face that looks even paler against her bright red lipstick. Her eyes are perpetually fixed on the screen of her iPhone, wrapped in a fluffy phone case in the shape of a bunny.

While the cashier counts her cash, Li snaps a short video of the scene and shares it with her social media followers.

Charlotte Fu for Chinarrative.

Li is not binge shopping or seeking attention out of self-indulgence. The young woman is a professional daigou (pronounced: “dye-go”), a personal shopper who purchases overseas goods for clients in China, typically for a 10 to 30 percent commission.

Daigou like Li are surrogate shoppers but are also, in a sense, purveyors of experience that allow more people the chance to have a quasi-Fifth Avenue shopping experience without leaving China.

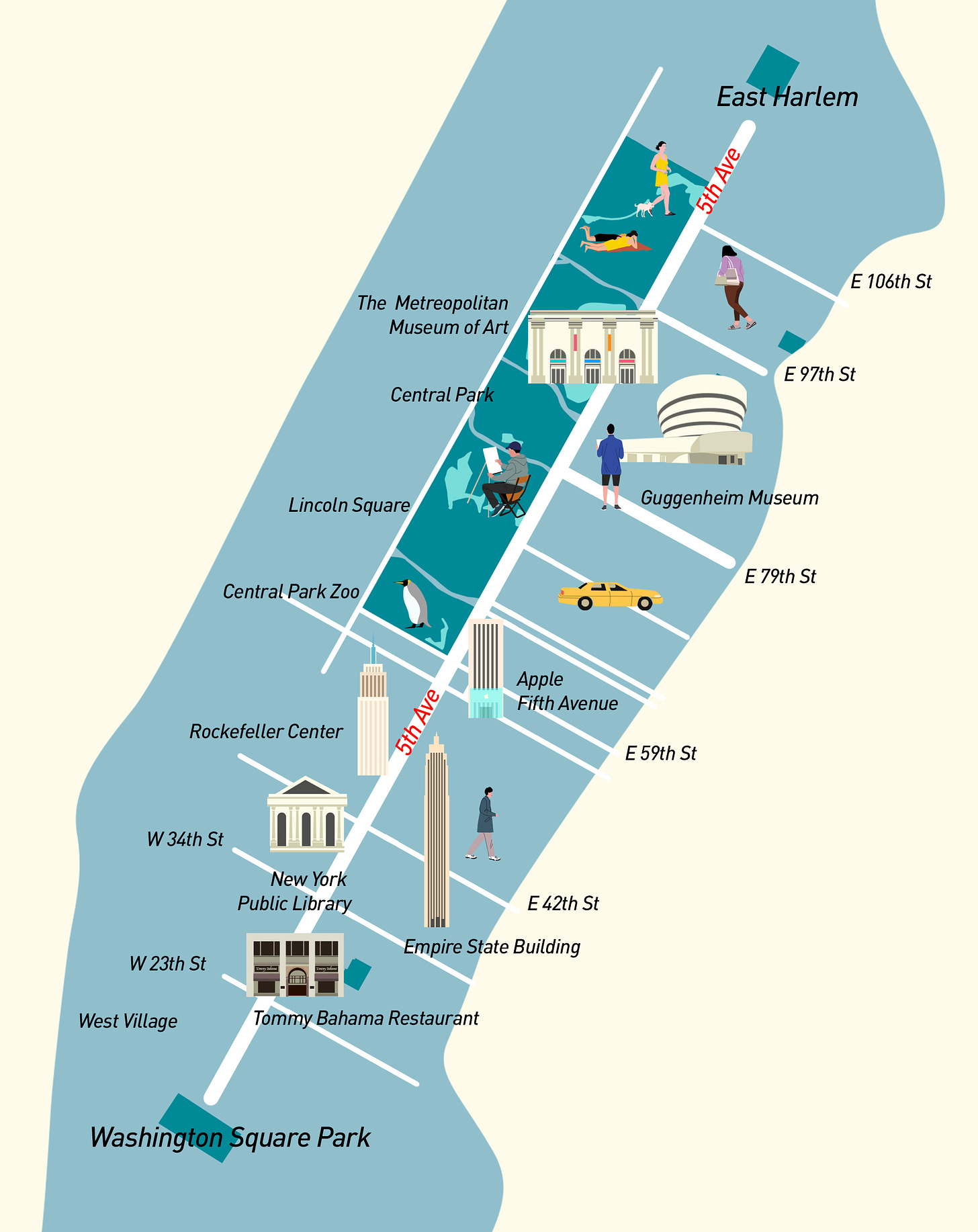

Like many daigou in the U.S., Li's main trade is designer handbags and, in particular, affordable luxury brands like Michael Kors, Coach, and Kate Spade, which all have stores on the same tony stretch of Fifth Avenue—but are also sold in outlet malls outside of the city.

Daigou were responsible for as much as $7.5 billion of sales in the luxury sector in 2015 worldwide, according to a report by management consultant Bain & Co—equivalent to nearly half of China's overall luxury purchases that year.

Charlotte Fu for Chinarrative.

Li operates her business exclusively on WeChat—China’s most popular messaging app, where over 3,000 people follow her. Li’s feed, filled with close-up pictures of purses and wide-angle shots of carefully curated wall displays, works as a digital catalogue for eager consumers.

Orders also come in through WeChat. Li makes many of the purchases at Woodbury Common Premium Outlets, one hour north of the city, and ships the products to China after she returns to Flushing in Queens, where she lives.

She goes to Woodbury most days of the week, catching a ride with her husband, a driver for a tour company that specializes in bringing Chinese tourists to the outlet mall.

On other days, she visits Saks Off Fifth or Macy’s in midtown Manhattan instead. In either case, as long as she is awake, she is constantly posting on WeChat and texting with clients.

Daigou, in the broadest sense of the word, started in the early 1980s, when China first began allowing its citizens to travel abroad. They brought back with them gifts and goods that were either unavailable back home or marked up with hefty duties.

Thanks to the rise of e-commerce and disposable incomes, daigou has since evolved into a billion-dollar global industry involving over a million Chinese overseas, and yet that very growth now threatens its continued existence.

According to statistics from China E-Commerce Research Center, by 2013, the daigou economy was worth $10 billion, up from about $177 million in 2008. A search for the term “US daigou” on popular Chinese social networks further reveals its scale.

In 2018, a query on Weibo, a microblog website often described as the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, turned up some 40,000 users while on online shopping platform Taobao, the same search returned more than 30,000 stores.

A survey by consultancy McKinsey & Co. in 2012 shows that 60 percent of Chinese consumers were willing to accept a 20 percent price markup on luxury products sold in China, while in 2017, only 20 percent of consumers said they would tolerate such markups.

The success of daigou is not surprising then, as these shoppers help Chinese consumers access foreign goods much more affordably.

Where Daigou Flourish

Flushing is home to New York City’s largest Chinese enclave, and daigou there number in at least the hundreds. The professional shoppers connect with each other on WeChat groups, with some of the more prolific daigou even supplying the others.

There, two key support services allow the daigou business to flourish: online-to-offline money exchange and delivery services. The neighborhood’s travel agencies, delis, internet cafes, and even barber shops allow daigou to exchange WeChat digital payments into hard American dollars.

Meanwhile, shipping stores help daigou send goods to China. Li’s go-to place is tucked away on a quiet corner a little west of Flushing’s Main Street, where two worn banners advertising baby formulas, supplements, and international shipping services (starting from $2.99 per pound) hang on the red-brick exterior of a tiny storefront.

Li stops in at the end of her shopping trip to Woodbury, near closing time. In a cramped space just a few feet wide, a man helps her pack the purses into repurposed Amazon boxes and seals them with brown duct tape, while two toddlers watch the scene in boredom.

“They’ll help you clear the customs too, and deliver right to the customers’ doors,” says Li. “I don’t have to worry about it.”

But this convenience operates in a legal grey area—at best.

Li’s cousin-in-law, a shopping tour guide who goes to Woodbury regularly, jokingly compares personal shoppers to smugglers.

“But so many people in Flushing do this on the side,” he says. “Students—at Columbia, NYU—do it, too. And daigou is a vague concept. Some shop only for friends back home. Would you count that as daigou, too?”

But for Qianyu Yang, a partner at a New York law firm specializing in serving the Chinese community, the legal risks of daigou are no joke. The way Li exchanges online money off line, she says:

It is essentially money laundering.

Matthew Dresden, partner at another law firm focusing on Chinese law for businesses, adds that the issues arise because “most of the daigou aren’t declaring the items.... when your business model is to avoid taxes and customs, that can be problematic.”

Credit: Alex Fang.

“It is virtually impossible to shut down the daigou network,” said Brian Buchwald, founder of Bomoda, a company that provides business intelligence on Chinese consumers.

He points out that personal shoppers occupy a sliver of the multibillion-dollar industry that, until recently, allowed it to go unnoticed.

This is especially true for daigou whose entire operation is contained within the private communications of WeChat. As active as Li is on the Chinese app, her business has remained off-the-radar of brands.

Clamping Down on Daigou

In August 2018, China passed its first e-commerce law, which seeks to regulate all online vendors, including those on social media channels like WeChat, which had previously managed to avoid regulation.

Under the new law, which took effect on Jan. 1, 2019, all daigou selling for profit, rather than personal use, are now required to obtain a business license.

But daigou may have been on its way out even before the new law was introduced. Will Tao, a director at Chinese consulting firm iResearch, said that due to lowered tariffs on overseas goods, the majority of cross-border e-commerce had already shifted toward JD.com and Tmall, the Taobao spin-off.

“Daigou is no longer the mainstay of Chinese overseas consumption,” he said.

The increased ease and affordability of foreign travel—to short-haul destinations like neighboring Japan and South Korea, or the separately governed Chinese territory of Hong Kong, if not North America and Europe—also threatens the daigou economy.

When I shadowed Li in early 2018, I asked her if she would like to be a daigou in the long run. She said she didn’t know.

A few minutes later, she asked me about what she would need to do to apply for a master’s program in the U.S. before talking about saving up for a down payment to buy a home.

Before returning to Flushing again that evening, the young woman had filled her husband’s van with just-purchased shopping bags.

“This is nothing,” she said, as her husband started the vehicle. “On a busy day, they could pile up all the way to the ceiling.”

By the time the van reached the Triborough Bridge, Li had fallen into a slumber. The next day, she would do it all over again.

* Sunny Li is a pseudonym.

Alex Fang is a journalist based in New York.